You are looking for information, articles, knowledge about the topic nail salons open on sunday near me how were the presidential administrations of harding and coolidge similar on Google, you do not find the information you need! Here are the best content compiled and compiled by the https://chewathai27.com team, along with other related topics such as: how were the presidential administrations of harding and coolidge similar harding vs coolidge, what were harding and coolidge’s policies, what did harding do as president, 6.14 quiz: the bubble bursts, 6.16 quiz: seeking solutions, what were coolidge’s nicknames?

Contents

How were the presidential administrations of Harding and Coolidge similar quizlet?

Terms in this set (2)

How were the presidential administrations of Harding and Coolidge similar? Both supported big business.

What was the Harding administration known for?

Harding also signed the Budget and Accounting Act, which established the country’s first formal budgeting process and created the Bureau of the Budget. Another major aspect of his domestic policy was the Fordney–McCumber Tariff, which greatly increased tariff rates.

What was president Coolidge known for?

Throughout his gubernatorial career, Coolidge ran on the record of fiscal conservatism and strong support for women’s suffrage. He held a vague opposition to Prohibition. During his presidency, he restored public confidence in the White House after the many scandals of his predecessor’s administration.

Who was the 30th president of the United States?

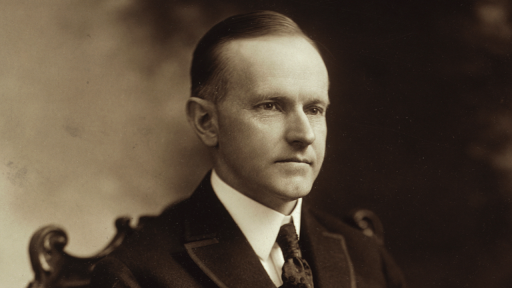

As America’s 30th President (1923-1929), Calvin Coolidge demonstrated his determination to preserve the old moral and economic precepts of frugality amid the material prosperity which many Americans were enjoying during the 1920s era.

What were Coolidge’s policies quizlet?

- limit international involvement for the us.

- no permanent ore telling alliances.

- keep US at peace.

- international agreements based on laws not military force.

What was a major problem during the Harding administration quizlet?

biggest scandal of Harding’s administration; Secretary of Interior Albert Fall illegally leased government oil fields in the West to private oil companies; Fall was later convicted of bribery and became the first Cabinet official to serve prison time (1931-1932).

What party was Coolidge?

How old do you have to be to be president?

Requirements to Hold Office

According to Article II of the U.S. Constitution, the president must be a natural-born citizen of the United States, be at least 35 years old, and have been a resident of the United States for 14 years.

What president died on July 4th?

It is a fact of American history that three Founding Father Presidents—John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Monroe—died on July 4, the Independence Day anniversary.

Who’s the 100th President?

Benjamin Harrison | The White House.

What President was born on July 4th?

John Calvin Coolidge—he would later drop the John completely—was born on July 4, 1872. Coolidge was a conservative’s conservative. He believed in small government and a good nap in the afternoon.

Who was the 50th President?

Clinton was born William Jefferson Blythe III on August 19, 1946, at Julia Chester Hospital in Hope, Arkansas. He is the son of William Jefferson Blythe Jr., a traveling salesman who had died in an automobile accident three months before his birth, and Virginia Dell Cassidy (later Virginia Kelley).

What was the primary difference in the economic policies of Presidents Warren G Harding and Calvin Coolidge quizlet?

What was the primary difference in the economic policies of presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge? Coolidge continued the pro-business policies of Harding’s administration. What accounted for the high rate of automobile sales in the 1920s?

What did the presidential election of 1924 in which Calvin Coolidge defeated John W Davis and Robert La Follette reveal about American voters quizlet?

What did the presidential election of 1924, in which Calvin Coolidge defeated John W. Davis and Robert La Follette, reveal about the priorities of American voter? The election results revealed voters’ lack of support for labor unions, the regulation of business, and the protection of civil liberties.

What were some of the issues and beliefs that rural and urban America clashed over in the 1920s?

what were some of the issues and beliefs that rural and urban america clashed over in the 1920’s? education was less important than the farm. bible was literally true. opposed modernism which opposed science.

What was the impact of the American plan and union related court rulings on unions in the 1920s?

What was the impact of the American Plan and union-related court rulings on unions in the 1920s? Union membership dropped by 2 million and became about 10 percent of the labor market. What factors caused the Great Depression? What explains the strong growth of the Ku Klux Klan during the 1920s?

brainly.com

- Article author: brainly.com

- Reviews from users: 29217

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.1

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about brainly.com Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolge were conservative politicians, and they had very similar views regarding economic policy. They both … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for brainly.com Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolge were conservative politicians, and they had very similar views regarding economic policy. They both …

- Table of Contents:

Presidency of Warren G. Harding – Wikipedia

- Article author: en.wikipedia.org

- Reviews from users: 5511

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.0

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Presidency of Warren G. Harding – Wikipedia Updating …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Presidency of Warren G. Harding – Wikipedia Updating

- Table of Contents:

Contents

1920 election[edit]

Inauguration[edit]

Administration[edit]

Judicial appointments[edit]

Domestic affairs[edit]

Foreign affairs[edit]

Administration scandals[edit]

Life at the White House[edit]

Western tour and death[edit]

Historical reputation[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Further reading[edit]

External links[edit]

Navigation menu

Calvin Coolidge – Wikipedia

- Article author: en.wikipedia.org

- Reviews from users: 23717

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.5

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Calvin Coolidge – Wikipedia Updating …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Calvin Coolidge – Wikipedia Updating

- Table of Contents:

Contents

Early life and family history

Early career and marriage

Local political office (1898−1915)

Lieutenant Governor and Governor of Massachusetts (1916−1921)

Vice presidency (1921−1923)

Presidency (1923−1929)

Post-presidency (1929–1933)

Radio film and commemorations

See also

Notes

References

Works cited

Further reading

External links

Navigation menu

Calvin Coolidge | The White House

- Article author: www.whitehouse.gov

- Reviews from users: 10540

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.0

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Calvin Coolidge | The White House Updating …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Calvin Coolidge | The White House Updating As America’s 30th President (1923-1929), Calvin Coolidge demonstrated his determination to preserve the old moral and economic precepts of frugality amid the material prosperity which many Americans were enjoying during the 1920s era.

- Table of Contents:

Mobile Menu Overlay

Stay Connected

How were the presidential administrations of Harding and Coolidge similar? | Study.com

- Article author: study.com

- Reviews from users: 35299

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.5

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about How were the presidential administrations of Harding and Coolidge similar? | Study.com Both Present Harding and Present Coolge were Republicans and were strong supporters of free market economics and low taxes. In many respects,. …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for How were the presidential administrations of Harding and Coolidge similar? | Study.com Both Present Harding and Present Coolge were Republicans and were strong supporters of free market economics and low taxes. In many respects,. Answer to: How were the presidential administrations of Harding and Coolidge similar? By signing up, you’ll get thousands of step-by-step solutions…How were the presidential administrations of Harding and Coolidge similar? | Study.com

- Table of Contents:

Question

Harding and Coolidge

Answer and Explanation

The Similarities and Differences Between Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge | Kibin

- Article author: www.kibin.com

- Reviews from users: 12890

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.9

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about The Similarities and Differences Between Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge | Kibin The two former presents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolge were alike in some ways and different in others. Present Harding was a news paper owner … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for The Similarities and Differences Between Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge | Kibin The two former presents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolge were alike in some ways and different in others. Present Harding was a news paper owner … The two former presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge were alike in some ways and different in others. President Harding was a news paper owner from Ohio. He was chosen as the Rep. candidate after serving as an Ohio senator. Calvin Coolidge was the Vice-president at the time of Wa…

- Table of Contents:

how were the presidential administrations of harding and coolidge similar

- Article author: www.hanover.k12.in.us

- Reviews from users: 3367

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.8

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about how were the presidential administrations of harding and coolidge similar Objective: The impact of the Harding and Coolge presencies on the 20’s. The Harding Presency. Warren G. Harding. Was a newspaper publisher; Grew up … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for how were the presidential administrations of harding and coolidge similar Objective: The impact of the Harding and Coolge presencies on the 20’s. The Harding Presency. Warren G. Harding. Was a newspaper publisher; Grew up …

- Table of Contents:

Prosperity and Thrift: The Coolidge Administration

- Article author: memory.loc.gov

- Reviews from users: 49238

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.3

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Prosperity and Thrift: The Coolidge Administration Coolge’s economic themes were given concrete form by the initiatives of … Mellon’s term of office spanned the administrations of Presents Harding, … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Prosperity and Thrift: The Coolidge Administration Coolge’s economic themes were given concrete form by the initiatives of … Mellon’s term of office spanned the administrations of Presents Harding, …

- Table of Contents:

Calvin Coolidge: the 30th President (article) | Khan Academy

- Article author: www.khanacademy.org

- Reviews from users: 47713

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.2

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Calvin Coolidge: the 30th President (article) | Khan Academy Harding had been a popular present, and the nation was shocked and saddened … In foreign policy, the Coolge administration was hesitant to cultivate … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Calvin Coolidge: the 30th President (article) | Khan Academy Harding had been a popular present, and the nation was shocked and saddened … In foreign policy, the Coolge administration was hesitant to cultivate … Calvin Coolidge presided over the Roaring Twenties.

- Table of Contents:

1920s America

1920s America

Site Navigation

Harding and Coolidge: Emergence of the Media Presidency | SpringerLink

- Article author: link.springer.com

- Reviews from users: 13316

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.1

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Harding and Coolidge: Emergence of the Media Presidency | SpringerLink Large portions of Harding’s presential papers were burned, heavily edited, or discarded after his death. … For overviews of the Harding administration,. …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Harding and Coolidge: Emergence of the Media Presidency | SpringerLink Large portions of Harding’s presential papers were burned, heavily edited, or discarded after his death. … For overviews of the Harding administration,. The 1920s often have been viewed as something of an interlude in the twentieth-century expansion of presidential management of public opinion through the news media. Republican candidate Warren G. Harding pledged in 1920 to lead the nation “back to…

- Table of Contents:

Abstract

Buying options

Preview

Notes

Copyright information

About this chapter

Buying options

Coolidge Chronology

- Article author: coolidgefoundation.org

- Reviews from users: 8850

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.2

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Coolidge Chronology According to business historian Robert Sobel, Harding and Coolge were quite different. Harding was out going and inquisitive, but not respected for his … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Coolidge Chronology According to business historian Robert Sobel, Harding and Coolge were quite different. Harding was out going and inquisitive, but not respected for his …

- Table of Contents:

See more articles in the same category here: 670+ tips for you.

Presidency of Warren G. Harding

U.S. presidential administration from 1921 to 1923

Warren G. Harding’s tenure as the 29th president of the United States lasted from March 4, 1921 until his death on August 2, 1923. Harding presided over the country in the aftermath of World War I. A Republican from Ohio, Harding held office during a period in American political history from the mid-1890s to 1932 that was generally dominated by his party. He died of an apparent heart attack and was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge.

Harding took office after defeating Democrat James M. Cox in the 1920 presidential election. Running against the policies of incumbent Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, Harding won the popular vote by a margin of 26.2 percentage points, which remains the largest popular-vote percentage margin in presidential elections since the end of the Era of Good Feelings in the 1820s. Upon taking office, Harding instituted conservative policies designed to minimize the government’s role in the economy. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon won passage of the Revenue Act of 1921, a major tax cut that primarily reduced taxes on the wealthy. Harding also signed the Budget and Accounting Act, which established the country’s first formal budgeting process and created the Bureau of the Budget. Another major aspect of his domestic policy was the Fordney–McCumber Tariff, which greatly increased tariff rates.

Harding supported the 1921 Emergency Quota Act, which marked the start of a period of restrictive immigration policies. He vetoed a bill designed to give a bonus to World War I veterans but presided over the creation of the Veterans Bureau. He also signed into law several bills designed to address the farm crisis and, along with Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, promoted new technologies like the radio and aviation. Harding’s foreign policy was directed by Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes. Hughes’s major foreign policy achievement was the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–1922, in which the world’s major naval powers agreed on a naval disarmament program. Harding appointed four Supreme Court justices, all of whom became conservative members of the Taft Court. Shortly after Harding’s death, several major scandals emerged, including the Teapot Dome scandal. Harding died as one of the most popular presidents in history, but the subsequent exposure of the scandals eroded his popular regard, as did revelations of several extramarital affairs. In historical rankings of the U.S. presidents, Harding is often rated among the worst.

1920 election [ edit ]

Republican nomination [ edit ]

By early 1920, General Leonard Wood, Illinois governor Frank Lowden, and Senator Hiram Johnson of California had emerged as the frontrunners for the Republican nomination in the upcoming presidential election.[1][2] Some in the party began to scout for such an alternative, and Harding’s name arose, despite his reluctance, due to his unique ability to draw vital Ohio votes.[3] Harry Daugherty, who became Harding’s campaign manager, and who was sure none of these candidates could garner a majority, convinced Harding to run after a marathon discussion of six-plus hours.[4] Daugherty’s strategy focused on making Harding liked by or at least acceptable to all wings of the party, so that Harding could emerge as a compromise candidate in the likely event of a convention deadlock.[5] He struck a deal with Oklahoma oilman Jake L. Hamon, whereby 18 Oklahoma delegates whose votes Hamon had bought for Lowden were committed to Harding as a second choice if Lowden’s effort faltered.[6][7]

By the time the 1920 Republican National Convention began in June, a Senate sub-committee had tallied the monies spent by the various candidates, with totals as follows: Wood – $1.8 million; Lowden – $414,000; Johnson – $194,000; and Harding – $114,000; the committed delegate count at the opening gavel was: Wood – 124; Johnson – 112; Lowden – 72; Harding – 39.[8] Still, at the opening, less than one-half of the delegates were committed,[9] and many expected the convention to nominate a compromise candidate like Pennsylvania Senator Philander C. Knox, Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, or 1916 nominee Charles Evans Hughes.[10] No candidate was able to corral a majority after nine ballots.[11] After the convention adjourned for the day, Republican Senators and other leaders, who were divided and without a singular political boss, met in Room 404 of the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago. After a nightlong session, these party leaders tentatively concluded Harding was the best possible compromise candidate; this meeting has often been described as having taken place in a “smoke-filled room.”[12] The next day, on the tenth ballot, Harding was nominated for president. Delegates then selected Massachusetts governor Calvin Coolidge to be his vice-presidential running mate.[13]

General election [ edit ]

Harding’s home in Marion, Ohio , from which he conducted his 1920 “front porch” campaign. (c.1918–1921)

Harding’s opponent in the 1920 election was Ohio governor and newspaperman James M. Cox, who had won the Democratic nomination in a 44-ballot convention battle. Harding rejected the Progressive ideology of the Wilson administration in favor of the laissez-faire approach of the McKinley administration.[14] He ran on the promise of a “return to normalcy,” calling for the end to an era which he saw as tainted by war, internationalism, and government activism.[15] He stated:

America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration; not agitation, but adjustment; not surgery, but serenity; not the dramatic, but the dispassionate; not experiment, but equipoise; not submergence in internationality, but sustainment in triumphant nationality.[16]

The 1920 election was the first in which women could vote nationwide, as well as the first to be covered on the radio.[17] Led by Albert Lasker, the Harding campaign executed a broad-based advertising campaign that used modern advertising techniques for the first time in a presidential campaign.[18] Using newsreels, motion pictures, sound recordings, billboard posters, newspapers, magazines, and other media, Lasker emphasized and enhanced Harding’s patriotism and affability. Five thousand speakers were trained by advertiser Harry New and sent across the country to speak for Harding. Telemarketers were used to make phone conferences with perfected dialogues to promote Harding, and Lasker had 8,000 photos of Harding and his wife distributed around the nation every two weeks. Farmers were sent brochures decrying the alleged abuses of Democratic agriculture policies, while African Americans and women were given literature in an attempt to take away votes from the Democrats.[19] Additionally, celebrities like Al Jolson and Lillian Russell toured the nation on Harding’s behalf.[20]

1920 electoral vote results

Harding won a decisive victory, receiving 404 electoral votes to Cox’s 127. He took 60 percent of the nationwide popular vote, the highest percentage ever recorded up to that time, while Cox received just 34 percent of the vote.[21] Campaigning from a federal prison, Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs received 3% percent of the national vote. Harding won the popular vote by a margin of 26.2%, the largest margin since the election of 1820. He swept every state outside of the “Solid South”, and his victory in Tennessee made him the first Republican to win a former Confederate state since the end of Reconstruction. In the concurrent congressional elections, the Republicans picked up 63 seats in the House of Representatives.[23] The incoming 67th Congress would be dominated by Republicans, though the party was divided among various factions, including an independent-minded farm bloc from the Midwest.

Inauguration [ edit ]

Inauguration of Warren G. Harding, March 4, 1921.

Harding was inaugurated as the nation’s 29th president on March 4, 1921, on the East Portico of the United States Capitol. Chief Justice Edward D. White administered the oath of office. Harding placed his hand on the Washington Inaugural Bible as he recited the oath. This was the first time that a U.S. president rode to and from his inauguration in an automobile.[25] In his inaugural address Harding reiterated the themes of his campaign, declaring:

My Countrymen: When one surveys the world about him after the great storm, noting the marks of destruction and yet rejoicing in the ruggedness of the things which withstood it, if he is an American he breathes the clarified atmosphere with a strange mingling of regret and new hope. … Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it.[26]

Literary critic H.L. Mencken was appalled, announcing that:

He writes the worst English I have ever encountered. It reminds me of a string of wet sponges; it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights.[27]

Administration [ edit ]

Cabinet [ edit ]

From left: Harding, Andrew W. Mellon, Harry M. Daugherty, Edwin Denby, Henry C. Wallace, James J. Davis, Charles Evans Hughes, Calvin Coolidge, John W. Weeks, Will H. Hays, Albert Fall, Herbert Hoover Harding and his first Cabinet, 1921From left: Harding, Andrew W. Mellon, Harry M. Daugherty, Edwin Denby, Henry C. Wallace, James J. Davis, Charles Evans Hughes, Calvin Coolidge, John W. Weeks, Will H. Hays, Albert Fall, Herbert Hoover

Harding selected numerous prominent national figures for his ten-person Cabinet. Henry Cabot Lodge, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, suggested that Harding appoint Elihu Root or Philander C. Knox as Secretary of State, but Harding instead selected former Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes for the position. Harding appointed Henry C. Wallace, an Iowan journalist who had advised Harding’s 1920 campaign on farm issues, as Secretary of Agriculture. After Charles G. Dawes declined Harding’s offer to become Secretary of the Treasury, Harding assented to Senator Boies Penrose’s suggestion to select Pittsburgh billionaire Andrew Mellon. Harding used Mellon’s appointment as leverage to win confirmation for Herbert Hoover, who had led the U.S. Food Administration under Wilson and who became Harding’s Secretary of Commerce.[5]

Rejecting public calls to appoint Leonard Wood as Secretary of War, Harding instead appointed Lodge’s preferred candidate, former Senator John W. Weeks of Massachusetts. He selected James J. Davis for the position of Secretary of Labor, as Davis satisfied Harding’s criteria of being broadly acceptable to labor but being opposed to labor leader Samuel Gompers. Will H. Hays, the chairman of the Republican National Committee, was appointed Postmaster General. Grateful for his actions at the 1920 Republican convention, Harding offered Frank Lowden the post of Secretary of the Navy. After Lowden turned down the post, Harding instead appointed former Congressman Edwin Denby of Michigan. New Mexico Senator Albert B. Fall, a close ally of Harding’s during their time in the Senate together, became Harding’s Secretary of the Interior.[5]

Although Harding was committed to putting the “best minds” on his Cabinet, he often awarded other appointments to those who had contributed to his campaign’s victory. Wayne Wheeler, leader of the Anti-Saloon League, was allowed by Harding to dictate who would serve on the Prohibition Commission.[28] Harding appointed Harry M. Daugherty as Attorney General because he felt he owed Daugherty for running his 1920 campaign. After the election, many people from the Ohio area moved to Washington, D.C., made their headquarters in a little green house on K Street, and would be eventually known as the “Ohio Gang”.[29] Graft and corruption charges permeated Harding’s Department of Justice; bootleggers confiscated tens of thousands cases of whiskey through bribery and kickbacks.[30] The financial and political scandals caused by the Ohio Gang and other Harding appointees, in addition to Harding’s own personal controversies, severely damaged Harding’s personal reputation and eclipsed his presidential accomplishments.[31]

Press corps [ edit ]

According to biographers, Harding got along better with the press than any other previous president, being a former newspaperman. Reporters admired his frankness, candor, and his confessed limitations. He took the press behind the scenes and showed them the inner circle of the presidency. In November 1921, Harding also implemented a policy of taking written questions from reporters during a press conference.[32]

Judicial appointments [ edit ]

Harding appointed four justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. After the death of Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, former President William Howard Taft lobbied Harding for the nomination to succeed White. Harding acceded to Taft’s request, and Taft joined the court in June 1921. Harding’s next choice for the Court was conservative former Senator George Sutherland of Utah, who had been a major supporter of Taft in 1912 and Harding in 1920. Sutherland succeeded John Hessin Clarke in September 1922 after Clarke resigned. Two Supreme Court vacancies arose in 1923 due to the death of William R. Day and the resignation of Mahlon Pitney. On Taft’s recommendation, Harding nominated railroad attorney and conservative Democrat Pierce Butler to succeed Day. Progressive senators like Robert M. La Follette unsuccessfully sought to defeat Butler’s nomination, but Butler was confirmed. On the advice of Attorney General Daugherty, Harding appointed federal appellate judge Edward Terry Sanford of Tennessee to succeed Pitney.[34] Bolstered by these appointments, the Taft Court upheld the precedents of the Lochner era and largely reflected the conservatism of the 1920s.[35]

The Justice Department in the Harding Administration selected 6 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, 42 judges to the United States district courts, and 2 judges to the United States Court of Customs Appeals.

Domestic affairs [ edit ]

Revenue Act of 1921 [ edit ]

Harding assumed office while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline known as the Depression of 1920–21. He strongly rejected proposals to provide for federal unemployment benefits, believing that the government should leave relief efforts to charities and local governments. He believed that the best way to restore economic prosperity was to raise tariff rates and reduce the government’s role in economic activities. His administration’s economic policy was formulated by Secretary of the Treasury Mellon, who proposed cuts to the excess profits tax and the corporate tax.[38] The central tenet of Mellon’s tax plan was a reduction of the surtax, a progressive income tax that only affected high-income earners. Mellon favored the wealthy holding as much capital as possible, since he saw them as the main drivers of economic growth. Congressional Republican leaders shared Harding and Mellon’s desire for tax cuts, and Republicans made tax cuts and tariff rates the key legislative priorities of Harding’s first year in office. Harding called a special session of the Congress to address these and other issues, and Congress convened in April 1921.

Despite opposition from Democrats and many farm state Republicans, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1921 in November, and Harding signed the bill into law later that month. The act greatly reduced taxes for the wealthiest Americans, though the cuts were not as deep as Mellon had favored. The act reduced the top marginal income tax rate from 73 percent to 58 percent, lowered the corporate tax from 65 percent to 50 percent, and provided for ultimate elimination of the excess profits tax.[44][45] Revenues to the treasury decreased substantially.[46]

Wages, profits, and productivity all made substantial gains during the 1920s, and economists have differed as to whether Revenue Act of 1921 played a major role in the strong period of economic growth after the Depression of 1920–21. Economist Daniel Kuehn has attributed the improvement to the earlier monetary policy of the Federal Reserve, and notes that the changes in marginal tax rates were accompanied by an expansion in the tax base that could account for the increase in revenue.[47] Libertarian historians Schweikart and Allen argue that Harding’s tax and economic policies in part “… produced the most vibrant eight year burst of manufacturing and innovation in the nation’s history,”[48] Recovery did not last long. Another economic contraction began near the end of Harding’s presidency in 1923, while tax cuts were still underway. A third contraction followed in 1927 during the next presidential term.[49] Some economists have argued that the tax cuts resulted in growing economic inequality and speculation, which in turn contributed to the Great Depression.

Fordney–McCumber Tariff [ edit ]

Like most Republicans of his era, Harding favored protective tariffs designed to shield American businesses from foreign competition. Shortly after taking office, he signed the Emergency Tariff of 1921, a stopgap measure primarily designed to aid American farmers suffering from the effects of an expansion in European farm imports.[52] The emergency tariff also protected domestic manufacturing, as it included a clause to prevent dumping by European manufacturers. Harding hoped to sign a permanent tariff into law by the end of 1921, but heated congressional debate over tariff schedules, especially between agricultural and manufacturing interests, delayed passage of such a bill.

In September 1922, Harding enthusiastically signed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act.[55] The protectionist legislation was sponsored by Representative Joseph W. Fordney and Senator Porter J. McCumber, and was supported by nearly every congressional Republican. The act increased the tariff rates contained in the previous Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act of 1913, to the highest level in the nation’s history. Harding became concerned when the agriculture business suffered economic hardship from the high tariffs. By 1922, Harding began to believe that the long-term effects of high tariffs could be detrimental to national economy, despite the short-term benefits.[56] The high tariffs established under Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover have historically been viewed as a contributing factor to the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[44][57]

Bureau of the Budget [ edit ]

Harding believed the federal government should be fiscally managed in a way similar to private sector businesses. He had campaigned on the slogan, “Less government in business and more business in government.”[59] As the House Ways and Means Committee found it increasingly difficult to balance revenues and expenditures, Taft had recommended the creation of a federal budget system during his presidency. Businessmen and economists coalesced around Taft’s proposal during the Wilson administration, and by 1920, both parties favored it. Reflecting this goal, in June 1921, Harding signed the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921.

The act established the Bureau of the Budget to coordinate the federal budgeting process.[61] At the head of this office was the presidential budget director, who was directly responsible to the president rather than to the Secretary of Treasury. The law also stipulated that the president must annually submit a budget to Congress, and all presidents since have had to do so.[62] Additionally, the General Accounting Office (GAO) was created to assure congressional oversight of federal budget expenditures. The GAO would be led by the Comptroller General, who was appointed by Congress to a term of fifteen years. Harding appointed Charles Dawes as the Bureau of the Budget’s first director. Dawes’s first year in office saw government spending reduced by $1.5 billion, a 25 percent reduction, and he presided over another 25 percent reduction the following year.[64]

Immigration restriction [ edit ]

In the first two decades of the 20th century, immigration to the United States had increased, with many of the immigrants coming from Southern Europe and Eastern Europe rather than Western Europe. Many Americans viewed these new immigrants with suspicion, and World War I and the First Red Scare further heightened nativist fears. The Per Centum Act of 1921, signed by Harding on May 19, 1921, reduced the numbers of immigrants to 3 percent of a country’s represented population based on the 1910 Census. The act, which had been vetoed by President Wilson in the previous Congress, also allowed unauthorized immigrants to be deported. Harding and Secretary of Labor James Davis believed that enforcement had to be humane, and Harding often allowed exceptions granting reprieves to thousands of immigrants.[66] Immigration to the United States fell from roughly 800,000 in 1920 to approximately 300,000 in 1922. Though the act was later superseded by the Immigration Act of 1924, it marked the establishment of the National Origins Formula.[66]

Veterans [ edit ]

Many World War I veterans were unemployed or otherwise economically distressed when Harding took office. To aid these veterans, the Senate considered passing a law that gave veterans a $1 bonus for each day they had served in the war. Harding opposed payment of a bonus to veterans, arguing that much was already being done for them and that the bill would “break down our Treasury, from which so much is later on to be expected.” The Senate sent the bonus bill back to committee, but the issue returned when Congress reconvened in December 1921. A bill providing a bonus, without a means of funding it, was passed by both houses in September 1922. Harding vetoed it, and the veto was narrowly sustained.

In August 1921, Harding signed the Sweet Bill, which established a new agency known as the Veterans Bureau. After World War I, 300,000 wounded veterans were in need of hospitalization, medical care, and job training. To handle the needs of these veterans, the new agency incorporated the War Risk Insurance Bureau, the Federal Hospitalization Bureau, and three other bureaus that dealt with veteran affairs.[70] Harding appointed Colonel Charles R. Forbes, a decorated war veteran, as the Veteran Bureau’s first director. The Veterans Bureau later was incorporated into the Veterans Administration and ultimately the Department of Veterans Affairs.[71]

Farm acts [ edit ]

Farmers were among the hardest hit during the Depression of 1920–21, and prices for farm goods collapsed. The presence of a powerful bipartisan farm bloc led by Senator William S. Kenyon and Congressman Lester J. Dickinson ensured that Congress would address the farm crisis. Harding established the Joint Commission on Agricultural Industry to make recommendations on farm policy, and he signed a series of farm- and food-related laws in 1921 and 1922. Much of the legislation emanated from President Woodrow Wilson’s 1919 Federal Trade Commission report, which investigated and discovered “manipulations, controls, trusts, combinations, or restraints out of harmony with the law or the public interest” in the meat packing industry. The first law was the Packers and Stockyards Act, which prohibited packers from engaging in unfair and deceptive practices. Two amendments were made to the Farm Loan Act of 1916 that President Wilson had signed into law, which had expanded the maximum size of rural farm loans. The Emergency Agriculture Credit Act authorized new loans to farmers to help them sell and market livestock. The Capper–Volstead Act, signed by Harding on February 18, 1922, protected farm cooperatives from anti-trust legislation. The Future Trading Act was also enacted, regulating puts and calls, bids, and offers on futures contracting. Later, on May 15, 1922, the Supreme Court ruled this legislation unconstitutional,[44] but Congress passed the similar Grain Futures Act in response. Though sympathetic to farmers and deferential to Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, Harding was uncomfortable with many of the farm programs since they relied on governmental action, and he sought to weaken the farm bloc by appointing Kenyon to a federal judgeship in 1922.

Highways and radio [ edit ]

Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover listening to a radio

During the 1920s, use of electricity became increasingly common, and mass production of the automobile stimulated industries such as highway construction, rubber, steel, and construction. Congress had passed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 to aid state road-building programs, and Harding favored a further expansion of the federal role in road construction and maintenance. He signed into law the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, which allowed states to select interstate and intercounty roads that would receive federal funds. From 1921 to 1923, the federal government spent $162 million on America’s highway system, infusing the U.S. economy with a large amount of capital.

Harding and Secretary of Commerce Hoover embraced the emerging medium of the radio. In June 1922, Harding became the first president that the American public heard on the radio, delivering a speech in honor of Francis Scott Key.[17] Secretary of Commerce Hoover took charge of the administration’s radio policy. He convened a conference of radio broadcasters in 1922, which led to a voluntary agreement for licensing of radio frequencies through the Commerce Department. Both Harding and Hoover believed that something more than an agreement was needed, but Congress was slow to act, not imposing radio regulation until 1927. Hoover hosted a similar conference on aviation, but, as with the radio, was unable to win passage of legislation that would have provided for regulation air travel.

Labor issues [ edit ]

Union membership had grown during World War I, and by 1920 union members constituted approximately one-fifth of the labor force. Many employers reduced wages after the war, and some business leaders hoped to destroy the power of organized labor in order to re-establish control over their employees. These policies led to increasing labor tension in the early 1920s. Widespread strikes marked 1922, as labor sought redress for falling wages and increased unemployment. In April, 500,000 coal miners, led by John L. Lewis, struck over wage cuts. Mining executives argued that the industry was seeing hard times; Lewis accused them of trying to break the union. Harding convinced the miners to return to work while a congressional commission looked into their grievances. He also sent out the National Guard and 2,200 deputy U.S. marshals to keep the peace.[82] On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad workers went on strike. Harding proposed a settlement that made some concessions, but management objected. Attorney General Daugherty convinced Judge James H. Wilkerson to issue a sweeping injunction to break up the strike. Although there was public support for the Wilkerson injunction, Harding felt it went too far, and had Daugherty and Wilkerson amend it. The injunction succeeded in ending the strike; however, tensions remained high between railroad workers and management for years.

By 1922, the eight-hour day had become common in American industry. One exception was in steel mills, where workers labored through a twelve-hour workday, seven days a week. Hoover considered this practice barbaric, and convinced Harding to convene a conference of steel manufacturers with a view to ending it. The conference established a committee under the leadership of U.S. Steel chairman Elbert Gary, which in early 1923 recommended against ending the practice. Harding sent a letter to Gary deploring the result, which was printed in the press, and public outcry caused the manufacturers to reverse themselves and standardize the eight-hour day.

African Americans [ edit ]

Harding spoke of equal rights in his speech when accepting the Republican nomination in 1920:

“No majority shall abridge the rights of a minority […] I believe the Black citizens of America should be guaranteed the enjoyment of all their rights, that they have earned their full measure of citizenship bestowed, that their sacrifices in blood on the battlefields of the republic have entitled them to all of freedom and opportunity, all of sympathy and aid that the American spirit of fairness and justice demands.”[85]

In June 1921, three days after the massive Tulsa race massacre President Harding spoke at the all-black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. “Despite the demagogues, the idea of our oneness as Americans has risen superior to every appeal to mere class and group,” Harding declared. “And so, I wish it might be in this matter of our national problem of races.” He honored Lincoln alumni who had been among the more than 367,000 black soldiers to fight in the Great War. One Lincoln graduate led the 370th U.S. Infantry, the “Black Devils.” Col. F.A. Denison was the sole black commander of a regiment in France. The President called education critical to solving the issues of racial inequality, but he challenged the students to shoulder their shared responsibility to advance freedom. The government alone, he said, could not magically “take a race from bondage to citizenship in half a century.” He spoke about Tulsa and offered up a simple prayer: “God grant that, in the soberness, the fairness, and the justice of this country, we never see another spectacle like it.”[86]

Notably in an age of severe racial intolerance during the 1920s, Harding did not hold any racial animosity, according to historian Carl S. Anthony.[87] In a speech on October 26, 1921, given in segregated Birmingham, Alabama Harding advocated civil rights for African Americans, becoming the first president to openly advocate black political, educational, and economic equality during the 20th century.[87] In the Birmingham speech, Harding called for African Americans to have equal educational opportunities and greater voting rights in the South. The white section of the audience listened in silence while the black section of the segregated audience cheered.[88] Harding, however, openly stated that he was not for black social equality in terms of racial mixing or intermarriage.[89] Harding also spoke on the Great Migration, stating that blacks migrating to the North and West to find employment had actually harmed race relations between blacks and whites.[89]

The three previous presidents had dropped African Americans from several government positions they had previously held, and Harding reversed this policy.[90] African Americans were appointed to high-level positions in the Departments of Labor and Interior, and numerous blacks were hired in other agencies and departments.[91] Trani and Wilson write that Harding did not emphasize appointing African Americans to positions they had traditionally held prior to Wilson’s tenure, partly out of a desire to court white Southerners. Harding also disappointed black supporters by not abolishing segregation in federal offices, and through his failure to comment publicly on the Ku Klux Klan.

Harding supported Congressman Leonidas Dyer’s federal anti-lynching bill, known as the Dyer Bill, which passed the House of Representatives in January, 1922.[94] When it reached the Senate floor in November 1922, it was filibustered by Southern Democrats, and Senator Lodge withdrew it so as to allow a ship subsidy bill Harding favored to be debated. Many blacks blamed Harding for the Dyer bill’s defeat; Harding biographer Robert K. Murray noted that it was hastened to its end by Harding’s desire to have the ship subsidy bill considered.

Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act [ edit ]

On November 21, 1921, Harding signed the Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act, the first major federal government social welfare program in the U.S. The law was sponsored by Julia Lathrop, America’s first director of the U.S. Children’s Bureau. The Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act funded almost 3,000 child and health centers, where doctors treated healthy pregnant women and provided preventive care to healthy children. Child welfare workers were sent out to make sure that parents were taking care of their children. Many women were given career opportunities as welfare and social workers. Although the law remained in effect only eight years, it set the trend for New Deal social programs during the 1930s.[96][97]

Deregulation [ edit ]

As part of Harding’s belief in limiting the government’s role in the economy, he sought to undercut the power of the regulatory agencies that had been created or strengthened during the Progressive Era. Among the agencies in existence when Harding came to office were the Federal Reserve (charged with regulating banks), the Interstate Commerce Commission (charged with regulating railroads) and the Federal Trade Commission (charged with regulating other business activities, especially trusts). Harding staffed the agencies with individuals sympathetic to business concerns and hostile to regulation. By the end of his tenure, only the Federal Trade Commission resisted conservative domination. Other federal organizations, like the Railroad Labor Board, also came under the sway of business interests. In 1921, Harding signed the Willis Graham Act, which effectively rescinded the Kingsbury Commitment and allowed AT&T to establish a monopoly in the telephone industry.

Release of political prisoners [ edit ]

Eugene Debs after release from prison by President Harding, visits the White House

On December 23, 1921 Harding released Socialist leader Eugene Debs from prison. Debs had been convicted under sedition charges brought by the Wilson administration for his opposition to the draft during World War I.[101] Despite many political differences between the two candidates, Harding commuted Debs’ sentence to time served, though he did not grant Debs an official presidential pardon. Debs’ failing health was a contributing factor for the release. Harding granted a general amnesty to 23 prisoners, alleged anarchists and socialists, who had been active during the First Red Scare.[44][102]

1922 mid-term elections [ edit ]

Entering the 1922 midterm congressional election campaign, Harding and the Republicans had followed through on many of their campaign promises. But some of the fulfilled pledges, like cutting taxes for the well-off, did not appeal to the electorate. The economy had not returned to normalcy, with unemployment at 11 percent, and organized labor was angry over the outcome of the strikes. In the 1922 elections, Republicans suffered major losses in both the House and the Senate. Though they kept control of both chambers, they retained only a narrow majority in the House at the start of the 68th Congress in 1923. The elections empowered the progressive wing of the party led by Robert La Follette, who began investigations into Harding administration.

Foreign affairs [ edit ]

European relations [ edit ]

Harding took office less than two years after the end of World War I, and his administration faced several issues in the aftermath of that conflict. Harding made it clear when he appointed Hughes as Secretary of State that the former justice would run foreign policy, a change from Wilson’s close management of international affairs. Harding and Hughes frequently communicated, and the president remained well-informed regarding the state of foreign affairs, but he rarely overrode any of Hughes’s decisions. Hughes did have to work within some broad outlines; after taking office, Harding hardened his stance on the League of Nations, deciding the U.S. would not join even a scaled-down version of the League.

With the Treaty of Versailles unratified by the Senate, the U.S. remained technically at war with Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Peacemaking began with the Knox–Porter Resolution, declaring the U.S. at peace and reserving any rights granted under Versailles. Treaties with Germany, Austria and Hungary, each containing many of the non-League provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, were ratified in 1921. This still left the question of relations between the U.S. and the League. Hughes’ State Department initially ignored communications from the League, or tried to bypass it through direct communications with member nations. By 1922, though, the U.S., through its consul in Geneva, was dealing with the League. The U.S. refused to participate in any League meeting with political implications, but it sent observers to sessions on technical and humanitarian matters. Harding stunned the capital when he sent to the Senate a message supporting the participation of the U.S. in the proposed Permanent Court of International Justice (also known as the “World Court”). His proposal was not favorably received by most senators, and a resolution supporting U.S. membership in the World Court was drafted and promptly buried in the Foreign Affairs Committee.[109]

By the time Harding took office, there were calls from foreign governments for the reduction of the massive war debt owed to the United States, and the German government sought to reduce the reparations that it was required to pay. The U.S. refused to consider any multilateral settlement. Harding sought passage of a plan proposed by Mellon to give the administration broad authority to reduce war debts in negotiation, but Congress, in 1922, passed a more restrictive bill. Hughes negotiated an agreement for Britain to pay off its war debt over 62 years at low interest, effectively reducing the present value of the obligations. This agreement, approved by Congress in 1923, set a pattern for negotiations with other nations. Talks with Germany on reduction of reparations payments would result in the Dawes Plan of 1924.

During World War I, the U.S. had been among the nations that had sent troops to Russia after the Russian Revolution. Afterwards, President Wilson refused to provide diplomatic recognition to Russia, which was led by a Communist government following the October Revolution. Commerce Secretary Hoover, with considerable experience of Russian affairs, took the lead on Russian policy. He supported aid to and trade with Russia, fearing U.S. companies would be frozen out of the Soviet market. When famine struck Russia in 1921, Hoover had the American Relief Administration, which he had headed, negotiate with the Russians to provide aid. According to historian George Herring, the American relief effort may have saved as many as 10 million people from starvation. U.S. businessman such as Armand Hammer invested in the Russian economy, but many of these investments failed due to various Russian restrictions on trade and commerce. Russian and (after the 1922 establishment of the Soviet Union) Soviet leaders hoped that these economic and humanitarian connections would lead to recognition of their government, but Communism’s extreme unpopularity in the U.S. precluded this possibility.[112]

Disarmament [ edit ]

At the end of World War I, the United States had the largest navy and one of the largest armies in the world. With no serious threat to the United States itself, Harding and his successors presided over the disarmament of the navy and the army. The army shrank to 140,000 men, while naval reduction was based on a policy of parity with Britain.[113] Seeking to prevent an arms race, Senator William Borah won passage of a congressional resolution calling for a 50 percent reduction of the American Navy, the British Navy, and the Japanese Navy. With Congress’s backing, Harding and Hughes began preparations to hold a naval disarmament conference in Washington.[114] The Washington Naval Conference convened in November 1921, with representatives from the U.S., Japan, Britain, France, Italy, China, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Secretary of State Hughes assumed a primary role in the conference and made the pivotal proposal—the U.S. would reduce its number of warships by 30 if Great Britain decommissioned 19 ships and Japan decommissioned 17 ships.[115] A journalist covering the conference wrote that “Hughes sank in thirty-five minutes more ships than all of the admirals of the world have sunk in a cycle of centuries.”[116]

The conference produced six treaties and twelve resolutions among the participating nations, which ranged from limiting the tonnage of naval ships to custom tariffs.[117] The United States, Britain, Japan, and France reached the Four-Power Treaty, in which each country agreed to respect the territorial integrity of one another in the Pacific Ocean. Those four powers as well as Italy also reached the Washington Naval Treaty, which established a ratio of battleship tonnage that each country agreed to respect. In the Nine-Power Treaty, each signatory agreed to respect the Open Door Policy in China, and Japan agreed to return Shandong to China.[118] The treaties only remained in effect until the mid-1930s, however, and ultimately failed. Japan eventually invaded Manchuria and the arms limitations no longer had any effect. The building of “monster warships” resumed and the U.S. and Great Britain were unable to quickly rearm themselves to defend an international order and stop Japan from remilitarizing.[119][120]

Latin America [ edit ]

Intervention in Latin America had been a minor campaign issue; Harding spoke against Wilson’s decision to send U.S. troops to the Dominican Republic, and attacked the Democratic vice presidential candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, for his role in the Haitian intervention. Secretary of State Hughes worked to improve relations with Latin American countries who were wary of the American use of the Monroe Doctrine to justify intervention; at the time of Harding’s inauguration, the U.S. also had troops in Cuba and Nicaragua. The troops stationed in Cuba to protect American interests were withdrawn in 1921, but U.S. forces remained in the other three nations through Harding’s presidency. In April 1921, Harding gained the ratification of the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty with Colombia, granting that nation $25,000,000 as settlement for the U.S.-provoked Panamanian revolution of 1903. The Latin American nations were not fully satisfied, as the U.S. refused to renounce interventionism, though Hughes pledged to limit it to nations near the Panama Canal and to make it clear what the U.S. aims were.

The U.S. had intervened repeatedly in Mexico under Wilson, and had withdrawn diplomatic recognition, setting conditions for reinstatement. The Mexican government under President Álvaro Obregón wanted recognition before negotiations, but Wilson and his final Secretary of State, Bainbridge Colby, refused. Both Hughes and Secretary of the Interior Fall opposed recognition; Hughes instead sent a draft treaty to the Mexicans in May 1921, which included pledges to reimburse Americans for losses in Mexico since the 1910 revolution there. Obregón was unwilling to sign a treaty before being recognized, and he worked to improve the relationship between American businesses and Mexico, reaching agreement with creditors and mounting a public relations campaign in the United States.[124] This had its effect, and by mid-1922, Fall was less influential than he had been, lessening the resistance to recognition. The two presidents appointed commissioners to reach a deal, and the U.S. recognized the Obregón government on August 31, 1923, just under a month after Harding’s death, substantially on the terms proffered by Mexico.

Administration scandals [ edit ]

When Harding assembled his administration following the 1920 election, he appointed several longtime allies and campaign contributors to prominent political positions in control of vast amounts of government money and resources. Some of the appointees used their new powers to exploit their positions for personal gain. Although Harding was responsible for making these appointments, it is unclear how much, if anything, Harding himself knew about his friends’ illicit activities. No evidence to date suggests that Harding personally profited from such crimes, but he was apparently unable to prevent them. “I have no trouble with my enemies”, Harding told journalist William Allen White late in his presidency, “but my damn friends, they’re the ones that keep me walking the floor nights!”[109] The only scandal which was openly discovered during Harding’s lifetime was in the Veteran’s Bureau.[126] Yet gossip about various scandals became rampant after the suicides of Charles Cramer and Jess Smith. Harding responded aggressively to all of this with a mixture of grief, anger and perplexity.[citation needed]

Teapot Dome [ edit ]

Albert B. Fall , Harding’s first Secretary of the Interior and the first former Cabinet member sent to prison

The most notorious scandal was Teapot Dome, most of which came to light after Harding’s death. This affair concerned an oil reserve in Wyoming that was covered by a teapot-shaped rock formation. For years, the country had taken measures to ensure the availability of petroleum reserves, particularly for the navy’s use.[127] On February 23, 1923, Harding issued Executive Order # 3797, which created the Naval Petroleum Reserve Number 4 in Alaska. By the 1920s, it was clear that petroleum was important to the national economy and security, and the reserve system was designed to keep the oil under government jurisdiction rather than subject to private claims.[128] Management of these reserves was the subject of multi-dimensional arguments—beginning with a turf battle between the Secretary of the Navy and the Interior Department.[129] The strategic reserves issue was also a debate topic between conservationists and the petroleum industry, as well as those who favored public ownership versus private control.[130] Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall brought to his office significant political and legal experience, in addition to heavy personal debt, incurred in his obsession to expand his personal estate in New Mexico. He also was an avid supporter of the private ownership and management of reserves.[131]

Fall contracted Edward Doheny of Pan American Corporation to build storage tanks in exchange for drilling rights. It later came to light that Doheny had made significant personal loans to Fall.[132] The secretary also negotiated leases for the Teapot Dome reserves to Harry Ford Sinclair of the Consolidated Oil Corporation in return for guaranteed oil reserves to the credit of the government. Again, it later emerged that Sinclair had personally made concurrent cash payments of over $400,000 to Fall.[131] These activities took place under the watch of progressive and conservationist attorney, Harry A. Slattery, acting for Gifford Pinchot and Robert La Follette.[133] Fall was ultimately convicted in 1931 of accepting bribes and illegal no-interest personal loans in exchange for the leasing of public oil fields to business associates.[134] In 1931, Fall was the first cabinet member in history imprisoned for crimes committed while in office.[135] Paradoxically, while Fall was convicted for taking the bribe, Doheny was acquitted of paying it.[136]

Justice Department [ edit ]

Harding’s appointment of Harry M. Daugherty as Attorney General received more criticism than any other. As Harding’s campaign manager, Daugherty’s Ohio lobbying and back room maneuvers with politicians were not considered the best qualifications.[137] Historian M. R. Werner referred to the Justice Department under Harding and Daugherty as “the den of a ward politician and the White House a night club”. On September 16, 1922, Minnesota Congressman Oscar E. Keller brought impeachment charges against Daugherty. On December 4, formal investigation hearings, headed by congressman Andrew J. Volstead, began against Daugherty. The impeachment process, however, stopped, since Keller’s charges that Daugherty protected interests in trust and war fraud cases could not be substantially proven.[138]

Daugherty, according to a 1924 Senate investigation into the Justice Department, authorized a system of graft between aides Jess Smith and Howard Mannington. Both Mannington and Smith allegedly took bribes to secure appointments, prison pardons, and freedom from prosecution. A majority of these purchasable pardons were directed towards bootleggers. Cincinnati bootlegger George L. Remus, allegedly paid Jess Smith $250,000 to not prosecute him. Remus, however, was prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to Atlanta prison. Smith tried to extract more bribe money from Remus to pay for a pardon. The prevalent question at the Justice Department was “How is he fixed?”[139] Another alleged scandal involving Daugherty concerned the Wright-Martin Aircraft Corp., which supposedly overcharged the federal government by $2.3 million on war contracts.[140] Captain Hazel Scaife tried to bring the company to trial, but was blocked by the Department of Justice. At this time, Daugherty was said to have owned stock in the company and was even adding to these holdings, though he was never charged in the matter.[141]

Daugherty hired William J. Burns to run the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation.[142] A number of inquisitive congressmen or senators found themselves the object of wire taps, rifled files, and copied correspondence.[143] Burns’ primary operative was Gaston B. Means, a reputed con man, who was known to have fixed prosecutions, sold favors, and manipulated files in the Justice Department.[144] Means, who acted independently, took direct instructions and payments from Jess Smith, without Burn’s knowledge, to spy on congressmen. Means hired a woman, Laura Jacobson, to spy on Senator Thaddeus Caraway, a critic of the Harding administration. Means also was involved with “roping” bootleggers.[138]

Daugherty remained in his position during the early days of the Calvin Coolidge administration, then resigned on March 28, 1924, amidst allegations that he accepted bribes from bootleggers. Daugherty was later tried and acquitted twice for corruption. Both juries hung—in one case, after 65 hours of deliberation. Daugherty’s famous defense attorney, Max Steuer, blamed all corruption allegations against Daugherty on Jess Smith, who by then had committed suicide.[145]

Jess W. Smith [ edit ]

Daugherty’s personal aide, Jess W. Smith, was a central figure in government file manipulation, paroles and pardons, influence peddling—and even served as bag man.[146] During Prohibition, pharmacies received alcohol permits to sell alcohol for medical purposes. According to Congressional testimony, Daugherty arranged for Jess Smith and Howard Mannington to sell these permits to drug company agents who really represented bootleggers. The bootleggers, having obtained a permit could buy cases of whiskey. Smith and Mannington split the permit sales profits. Approximately 50,000 to 60,000 cases of whiskey were sold to bootleggers at a net worth of $750,000 to $900,000. Smith supplied bootleg whiskey to the White House and the Ohio Gang house on K Street, concealing the whiskey in a briefcase for poker games.[30][147]

Eventually, rumors of Smith’s abuses—free use of government cars, going to all night parties, manipulation of Justice Department files—reached Harding. Harding withdrew Smith’s White House clearance and Daugherty told him to leave Washington. On May 30, 1923, Smith’s dead body was found at Daugherty’s apartment with a gunshot wound to the head. William J. Burns immediately took Smith’s body away and there was no autopsy. Historian Francis Russell, concluding this was a suicide, indicates that a Daugherty aide entered Smith’s room moments after a noise awoke him, and found Smith on the floor with his head in a trash can and a revolver in his hand. Smith allegedly purchased the gun from a hardware store shortly before his death, after Daugherty verbally abused him for waking him up from a nap.[148][149]

Veterans’ bureau [ edit ]

Charles R. Forbes, the energetic Director of the Veterans Bureau, disregarded the dire needs of wounded World War I veterans to procure his own wealth.[150] After his appointment, Forbes convinced Harding to issue executive orders that gave him control over veterans’ hospital construction and supplies.[126] To limit corruption in the Veterans’ Bureau, Harding insisted that all government contracts be by public notice, but Forbes provided inside information to his co-conspirators to ensure their bids succeeded.[71] Forbes’ main task at the Veterans bureau, having an unprecedented $500 million yearly budget, was to ensure that new hospitals were built around the country to help the 300,000 wounded World War I veterans.[151] Forbes defrauded the government of an estimated $225 million by increasing construction costs from $3,000 to $4,000 per hospital bed.[152]

In early 1922, Forbes went on tours, known as joy-rides, of new hospital construction sites around the country and the Pacific Coast. On these tours, Forbes allegedly received traveling perks and alcohol kickbacks, took a $5,000 bribe in Chicago, and made a secret code to ensure $17 million in government construction hospital contracts with corrupt contractors.[153] Intent on making more money, on his return to the U.S. Capitol Forbes immediately began selling valuable hospital supplies under his control in large warehouses at the Perryville Depot.[154] The government had stockpiled huge amounts of hospital supplies during the first World War, which Forbes unloaded for a fraction of their cost to the Boston firm of Thompson and Kelly.[155][156] Charles F. Cramer, Forbes’ legal council to the Veterans Bureau, rocked the nation’s capital when he committed suicide in 1923.[157][158] Cramer, at the time of his death, was being investigated by a Senate committee on charges of corruption.[159][160]

Forbes faced resistance in the form of General Charles E. Sawyer, chairman of the Federal Hospitalization Board, who represented controlling interests in the valuable hospital supplies.[161] Sawyer, who was also Harding’s personal physician, told Harding that Forbes was selling valuable hospital supplies to an insider contractor.[162] After issuing two orders for the sales to stop, Harding finally summoned Forbes to the White House and demanded Forbes’ resignation, since Forbes had been insubordinate in not stopping the shipments.[163] Harding, however, was not yet ready to announce Forbes’ resignation and let him flee to Europe on the “flimsy pretext” that he would help disabled U.S. Veterans in Europe.[164][165] Harding placed a reformer, Brigadier General Frank T. Hines, in charge of the Veterans Bureau. Hines immediately cleared up the mess left by Forbes. When Forbes returned to the U.S., he visited Harding at the White House in the Red Room. During the meeting, Harding angrily grabbed Forbes by the throat, shook him vigorously, and exclaimed “You double-crossing bastard!”[166] In 1926, Forbes was brought to trial and convicted of conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government. He received a two-year prison sentence and was released in November 1927.[167]

Other agencies [ edit ]

On June 13, 1921, Harding appointed Albert D. Lasker chairman of the United States Shipping Board. Lasker, a cash donor and Harding’s general campaign manager, had no previous experience with shipping companies. The Merchant Marine Act of 1920 had allowed the Shipping Board to sell ships made by the U.S. Government to private American companies. A congressional investigation revealed that while Lasker was in charge, many valuable steel cargo ships, worth between $200 and $250 a ton, were sold for as low as $30 a ton to private American shipping companies without an appraisal board. J. Harry Philbin, a manager in the sales division, testified at the congressional hearing that under Lasker’s authority U.S. ships were sold, “…as is, where is, take your pick, no matter which vessel you took.” Lasker resigned from the Shipping Board on July 1, 1923.[168]

Thomas W. Miller, head of the Office of Alien Property, was convicted of accepting bribes. Miller’s citizenship rights were taken away and he was sentenced to 18 months in prison and a $5,000 fine. After Miller served 13 months of his sentence, he was released on parole. President Herbert Hoover restored Miller’s citizenship on February 2, 1933.[169] Roy Asa Haynes, Harding’s Prohibition Commissioner, ran the patronage-riddled Prohibition bureau, which was allegedly corrupt from top to bottom.[170] The bureau’s “B permits” for liquor sales became tantamount to negotiable securities, as a result of being so widely bought and sold among known violators of the law.[171] The bureau’s agents allegedly made a year’s salary from one month’s illicit sales of permits.[170]

Life at the White House [ edit ]

Harding’s lifestyle at the White House was fairly unconventional compared to his predecessor. Upstairs at the White House, in the Yellow Oval Room, Harding allowed bootleg whiskey to be freely served to his guests during after-dinner parties at a time when the President was supposed to enforce Prohibition. One witness, Alice Longworth, stated that trays, “…with bottles containing every imaginable brand of whiskey stood about.”[172] Some of this alcohol had been directly confiscated from the Prohibition department by Jess Smith, assistant to U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty. Mrs. Harding, also known as the “Duchess”, mixed drinks for the guests.[147] Harding played poker twice a week, smoked and chewed tobacco. Harding allegedly won a $4,000 pearl necktie pin at one White House poker game.[173] Although criticized by Prohibitionist advocate Wayne B. Wheeler over Washington, D.C. rumors of these “wild parties”, Harding claimed his personal drinking inside the White House was his own business.[174] Though Mrs. Harding did keep a little red book of those who had offended her, the executive mansion was now once again open to the public for events including the annual Easter egg roll.[175]

Western tour and death [ edit ]

Western tour [ edit ]

Harding aboard the presidential train in Alaska, with secretaries Hoover, Wallace, Work, and Mrs. Harding

Though Harding wanted to run for a second term, his health began to decline during his time in office. He gave up drinking, sold his “life-work,” the Marion Star, in part to regain $170,000 previous investment losses, and had Daugherty make him a new will. Harding, along with his personal physician Dr. Charles E. Sawyer, believed getting away from Washington would help relieve the stress of being president. By July 1923, criticism of the Harding Administration was increasing. Prior to his leaving Washington, the president reported chest pains that radiated down his left arm.[176][177] In June 1923, Harding set out on a journey, which he dubbed the “Voyage of Understanding”. The president planned to cross the country, go north to Alaska Territory, journey south along the West Coast, then travel by navy ship through the Panama Canal, to Puerto Rico, and to return to Washington at the end of August. The trip would allow him to speak widely across the country in advance of the 1924 campaign, and allow him some rest away from Washington’s oppressive summer heat.

Harding’s political advisers had given him a physically demanding schedule, even though the president had ordered it cut back. In Kansas City, Harding spoke on transportation issues; in Hutchinson, Kansas, agriculture was the theme. In Denver, he spoke on Prohibition, and continued west making a series of speeches not matched by any president until Franklin Roosevelt. In addition to making speeches, he visited Yellowstone and Zion National Parks, and dedicated a monument on the Oregon Trail at a celebration organized by venerable pioneer Ezra Meeker and others. On July 5, Harding embarked on USS Henderson in Washington state. The first president to visit Alaska, he spent hours watching the dramatic landscapes from the ship’s deck. After several stops along the coast, the presidential party left the ship at Seward to take the Alaska Central Railway to McKinley Park and Fairbanks, where he addressed a crowd of 1,500 in 94 °F (34 °C) heat. The party was to return to Seward by the Richardson Trail but due to Harding’s fatigue, it went by train.

Arriving via Vancouver Harbor on July 26, Harding became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Canada. He was greeted dock-side by the premier of British Columbia John Oliver and the mayor of Vancouver. Thousands lined the streets of Vancouver to watch as the motorcade of dignitaries moved through the city to Stanley Park, where Harding spoke to an audience estimated at over 40,000. In his speech he proclaimed, “You are not only our neighbor, but a very good neighbor, and we rejoice in your advancement and admire your independence no less sincerely than we value your friendship.”[186] Harding also visited a golf course, but completed only six holes before being fatigued. He was not successful in hiding his exhaustion; one reporter deemed him so tired a rest of mere days would not be sufficient to refresh him.

Death [ edit ]

The funeral procession for President Harding passes by the front of the White House

Upon returning to the U.S. on July 27, Harding participated in a series of events in Seattle. After reviewing the navy fleet in the harbor and riding in a parade through downtown, he addressed a crowd of over 30,000 Boy Scouts at a jamboree in Woodland Park and then addressed 25,000 people at the University of Washington’s Husky Stadium. That evening, in what would be his last official public event, Harding addressed the Seattle Press Club.[188] By the end of the evening Harding was near collapse, and he went to bed early. The next day, all tour stops scheduled between Seattle and San Francisco were cancelled, and the presidential entourage proceeded directly there.[186] Arriving in the city on the morning of July 29, Harding felt well enough that he insisted on walking from the train to the car. However, shortly after arriving at the Palace Hotel he suffered a relapse. Upon examining him, doctors found that not only was Harding’s heart causing problems, but he also had a serious case of pneumonia. All public engagements were cancelled.[citation needed]

When treated with caffeine and digitalis, Harding seemed to improve.[186] Reports that the released text of his July 31 speech had received a favorable reception also buoyed his spirits, and by the afternoon of August 2, doctors allowed him to sit up in bed. That evening, around 7:30 pm, while Florence Harding was reading a flattering article to the president from The Saturday Evening Post titled “A Calm Review of a Calm Man”,[190] he began twisting convulsively and collapsed. Doctors attempted stimulants, but were unable to revive him, and President Harding died at the age of 57. Although initially attributed to a cerebral hemorrhage, the president’s death was most likely the result a heart attack.[191][192]

Harding’s death came as a great shock to the nation. The president was liked and admired, and the press and public had followed his illness closely, and been reassured by his apparent recovery. Harding was returned to his train in a casket for a journey across the nation followed closely in the newspapers. Nine million people lined the tracks as Harding’s body was taken from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., and after services there, home to Marion, Ohio, for burial. In Marion, Warren Harding’s body was placed on a horse-drawn hearse, which was followed by President Coolidge and Chief Justice Taft, then by Harding’s wife and father. They followed it through the city, past the Star building where the presses stood silent, and at last to the Marion Cemetery, where the casket was placed in the cemetery’s receiving vault.

Immediately after Harding’s death, Mrs. Harding returned to Washington, D.C. and, according to historian Francis Russell, burned as much of President Harding’s correspondence and documents, both official and unofficial, as she could get.[198] However, most of Harding’s papers survived because Harding’s personal secretary, George Christian, disobeyed Florence Harding’s instructions.[199]

Historical reputation [ edit ]