You are looking for information, articles, knowledge about the topic nail salons open on sunday near me how to write jade in japanese on Google, you do not find the information you need! Here are the best content compiled and compiled by the https://chewathai27.com team, along with other related topics such as: how to write jade in japanese jade in japanese hiragana, jade in japanese katakana, japanese to english, hisui name meaning, jade in korean, jade in chinese, japanese word for jade dragon, jade in spanish

Contents

How do I write my name in Japanese style?

To write your name in Japanese, the easiest way is to find a Katakana letter that corresponds to the pronunciation of your Japanese name. For example, if your name is “Maria,” look for the Katakana character for Ma, which is マ, then the character for Ri, which is リ, and then character for A, which is ア.

Does Japan have Jade?

Japan is an important source of jadeite, much of which comes from the Itoigawa and Omi regions in Niigata Prefecture. The Kotaki area upstream of the Hime River in Itoigawa-Omi was the first documented source of gem-quality jadeite and jadeite-bearing rocks in Japan (Kawano, 1939; Ohmori, 1939).

How Japanese names are written?

Japanese names are usually written in kanji script, which are symbols that represent words or ideas. These characters can have different pronunciations depending on the context. However, some given names may also be written in the phonetic syllabary of hiragana or katakana.

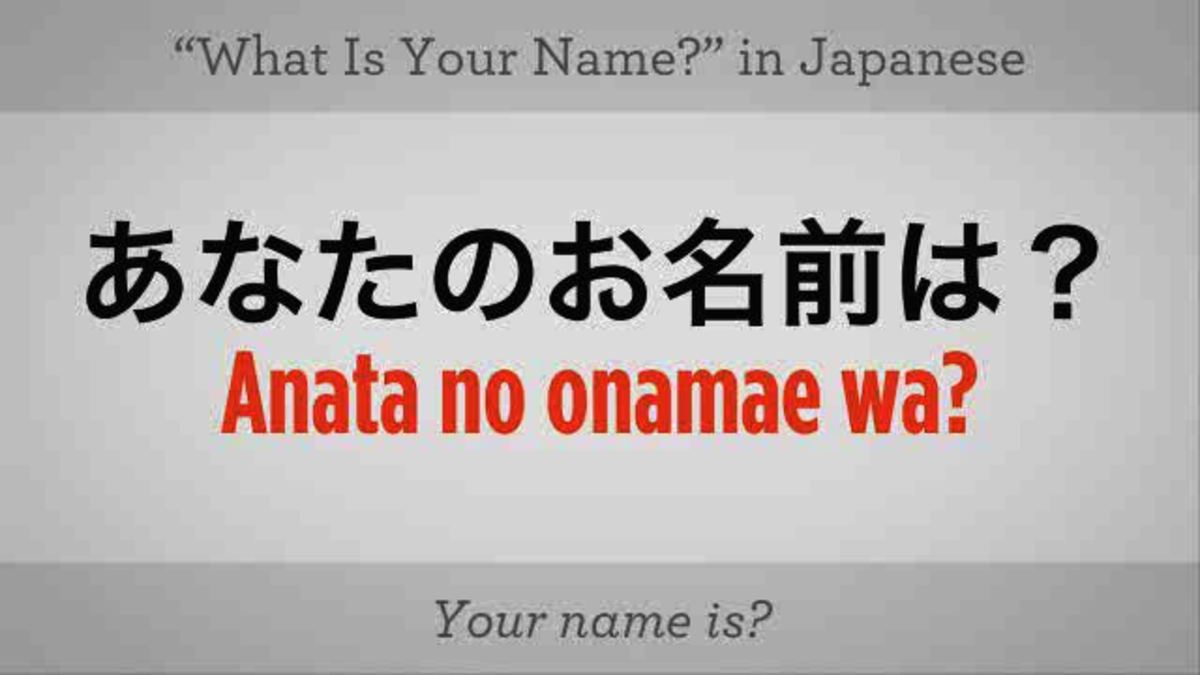

What is my name in Japanese language?

Anata no onamae wa? And that’s how to ask, “What is your name?” in Japanese.

How do you write Z in Japanese?

ゼット is the most common pronunciation for Z. ズィー is used by younger generation or by realists, but elderly and conservative people may not understand it. ゼッド is rare.

What is the letter S in Japanese?

| A | I | |

|---|---|---|

| S | さ | し |

| T | た | ち |

| N | な | に |

| H | は | ひ |

What jade means?

Jade is a symbol of serenity and purity. It signifies wisdom gathered in tranquility. It increases love and nurturing. A protective stone, Jade keeps the wearer from harm and brings harmony. Jade attracts good luck and friendship.

Is jade Japanese or Chinese?

It is the national stone of Japan. Examples of use in Japan can be traced back to the early Jomon period about 7,000 years ago. XRF analysis results have revealed that all jade used in Japan since the Jomon period is from Itoigawa.

What color is jade?

Color is jadeite’s most important value factor. Because consumers traditionally associate jadeite with the color green, it surprises some people to learn that it comes in other colors as well—lavender, red, orange, yellow, brown, white, black, and gray. All of these colors can be attractive.

What is a cute Japanese name?

1. Aika – This cute girls’ name means “love song”. 2. Aimi – Japanese name meaning “love, beauty”. 3.

What is the prettiest Japanese name?

- Itsuki | 一喜 …

- Sora | 天 …

- Hana | 初夏 …

- Kaito | 海人 …

- Sayo | 沙世 …

- Takashi | 隆 Takashi is a masculine name that has been around for a long time. …

- Chiha | 千羽 Chiha is a name for girls. …

- Sakura | 桜 Like the pink and white blossoms that are its namesake, Sakura is a beautiful Japanese female given name.

What is a good anime name?

- Akane. “ Deep red”

- Asuka. From the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion, Asuka Langley Soryu is a powerhouse. …

- Aya. …

- Chiyoko. …

- Chouko. …

- Hana. …

- Hikari. “ …

- Hinata.

Is your name Japanese?

Your Name (Japanese: 君の名は。, Hepburn: Kimi no Na wa.) is a 2016 Japanese animated romantic fantasy film produced by CoMix Wave Films and distributed by Toho.

What is your age in Japan?

Since the solar calendar is used in Japan now and the Japanese calendar corresponds to the Christian calendar, the method of counting a person’s age in the traditional Japanese system will be as follows: ‘traditional Japanese system = your age + two‘ as for the period from the New Year’s Day until the day before …

What’s your name in Korean?

“What is your name?” in Korean

이름이 뭐야?

How do you type katakana N?

Press the Alt and “~” keys (the tilde key left of the “1” key) to quickly switch between English and Japanese input. If you have a Japanese keyboard, you can simply press the 半角/全角 key, also located left of the “1” key. Press the F7 key after you type something to quickly change it into Katakana.

Does Japan have an alphabet?

The Japanese alphabet is really three writing systems that work together. These three systems are called hiragana, katakana and kanji. If that sounds overwhelming, don’t worry!

Write Your Name In Japanese – Learn How to Write Your Name in Japanese – LearnJapanese123

- Article author: learnjapanese123.com

- Reviews from users: 27100

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.5

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Write Your Name In Japanese – Learn How to Write Your Name in Japanese – LearnJapanese123 Updating …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Write Your Name In Japanese – Learn How to Write Your Name in Japanese – LearnJapanese123 Updating If you want learn write your name in Japanese then visit LearnJapanese123. Here you can get the guidance and knowledge to write your name in Japanese. Visit us now!If you’re learning Japanese, one of the first things you should learn is how to introduce yourself! And you can’t do that unless you know your name in Japanese, right? Here is how to write your name…

- Table of Contents:

Japanese Jadeite: History, Characteristics, and Comparison with Other Sources | Gems & Gemology

- Article author: www.gia.edu

- Reviews from users: 17810

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.8

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Japanese Jadeite: History, Characteristics, and Comparison with Other Sources | Gems & Gemology Updating …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Japanese Jadeite: History, Characteristics, and Comparison with Other Sources | Gems & Gemology Updating Examines the sources, color, texture, and chemical composition of jadeite from Japanese deposits.jadeite, jade, Japan, Itoigawa, Omi, Itoigawa-Omi, Niigata, Wakasa, Tottori, chromophores, magatama, Renge belt, Sangun belt, Hokkaido, Sanbagawa belt, Kochi, Nagasaki, lavender, electron microprobe, LA-ICP-MS, chondrite normalized, primitive mantle normalized, Guatemala, Motagua, Myanmar, Kachin, Russia, Polar Urals, Abduriyim, Saruwatari, Katsurada

- Table of Contents:

Please choose a language

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

JADEITE FROM JAPANESE LOCALITIES

SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS AND ANALYTICAL METHODS

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

Japanese Jadeite: History, Characteristics, and Comparison with Other Sources | Gems & Gemology

- Article author: culturalatlas.sbs.com.au

- Reviews from users: 32367

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.4

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Japanese Jadeite: History, Characteristics, and Comparison with Other Sources | Gems & Gemology Updating …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Japanese Jadeite: History, Characteristics, and Comparison with Other Sources | Gems & Gemology Updating Examines the sources, color, texture, and chemical composition of jadeite from Japanese deposits.jadeite, jade, Japan, Itoigawa, Omi, Itoigawa-Omi, Niigata, Wakasa, Tottori, chromophores, magatama, Renge belt, Sangun belt, Hokkaido, Sanbagawa belt, Kochi, Nagasaki, lavender, electron microprobe, LA-ICP-MS, chondrite normalized, primitive mantle normalized, Guatemala, Motagua, Myanmar, Kachin, Russia, Polar Urals, Abduriyim, Saruwatari, Katsurada

- Table of Contents:

Please choose a language

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

JADEITE FROM JAPANESE LOCALITIES

SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS AND ANALYTICAL METHODS

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

How to Ask “What Is Your Name?” in Japanese – Howcast

- Article author: www.howcast.com

- Reviews from users: 45618

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.4

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about How to Ask “What Is Your Name?” in Japanese – Howcast Updating …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for How to Ask “What Is Your Name?” in Japanese – Howcast Updating Transcript How to ask, “What is your name?” in Japanese. Onamae wa nandesuka? Let’s try it. Onamae wa nandesuka? Onamae wa nandesuka? You can alsoHow to Learn Japanese,Money & Education

- Table of Contents:

How to Say Excuse Me in Japanese

How to Say Hello in Japanese

How to Say Yes & No in Japanese

How to Say Please in Japanese

How to Say Goodbye in Japanese

How to Say Happy Birthday in Japanese

How to Ask Do You Speak English in Japanese

How to Ask How Are You in Japanese

How to Ask Where Is the Bathroom in Japanese

How to Ask How Much Does This Cost in Japanese

How to Ask Why in Japanese

How to Ask Where Is in Japanese

How to Ask Where Are You From in Japanese

How to Ask Someone Out in Japanese

How to Ask for Someone’s Phone Number in Japanese

How to Ask for Directions in Japanese

How to Ask for the Check in Japanese

How to Apologize in Japanese

How to Speak to Someone on the Phone in Japanese

How to Answer the Phone in Japanese

How to Say I Don’t Understand Japanese in Japanese

How to Say I Love You in Japanese

How to Say My Name Is in Japanese

How to Say Shut Up in Japanese

How to Say I’m Sorry in Japanese

Arts & Crafts

Dance & Entertainment

Food & Drink

Health & Wellness

Home & Garden

Love & Relationships

Money & Education

Parenting & Pets

Personal Care & Style

Sports & Fitness

Tech & Gadgets

Video Games

Jade how to write in Japanese Kanji | Kanji Zone

- Article author: www.kanjizone.com

- Reviews from users: 16237

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.9

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about

Jade how to write in Japanese Kanji | Kanji Zone

Jade in Kanji (pronounced in Japanese: je-e-do). 慈恵土. Select alternate kanji: ji: 慈 (mercy), 志 (intention), 路 (road, route), 時 (time) … … - Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for

Jade how to write in Japanese Kanji | Kanji Zone

Jade in Kanji (pronounced in Japanese: je-e-do). 慈恵土. Select alternate kanji: ji: 慈 (mercy), 志 (intention), 路 (road, route), 時 (time) … Jade how to write in Kanji. Kanji name in personalized pendants and in custom products.Kanji name, your name in kanji, kanj, name translation, name in Japanese - Table of Contents:

Jade

in Katakana

Jade

in Hiragana

Personalised products

Customizable Zazzle products

Your Japanese Virtual Tattoo

Jade (jeido) in Japanese Katakana | YourKatakana

- Article author: yourkatakana.com

- Reviews from users: 42300

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.2

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Jade (jeido) in Japanese Katakana | YourKatakana The name Jade in Japanese Katakana is ジェイド which in romaji is jeo. Katakana is the standard translation for names into Japanese, Jade in Japanese … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Jade (jeido) in Japanese Katakana | YourKatakana The name Jade in Japanese Katakana is ジェイド which in romaji is jeo. Katakana is the standard translation for names into Japanese, Jade in Japanese … The name Jade, in Japanese Katakana is ã¸ã§ã¤ã or which in romaji is jeido. Jade in Japanese Hiragana, is ãããã©.

- Table of Contents:

Jade in Katakana

Jade in Romaji

Jade in Hiragana

Translate another name into Japanese Katakana

Names similar to Jade

Genuine Jade in Chinese & Japanese Kanji Handmade Scrolls

- Article author: www.orientaloutpost.com

- Reviews from users: 28359

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.4

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Genuine Jade in Chinese & Japanese Kanji Handmade Scrolls ジェイド is the name Jade in Japanese. ジェイド is meant to sound like the English pronunciation of jade. It does not mean jade. Note: Because this title is … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Genuine Jade in Chinese & Japanese Kanji Handmade Scrolls ジェイド is the name Jade in Japanese. ジェイド is meant to sound like the English pronunciation of jade. It does not mean jade. Note: Because this title is … Amazing Jade Custom Wall Scrolls in Chinese or Japanese. We create handcrafted Jade calligraphy wall scrolls at discount prices.Search for Jade Japanese Chinese Calligraphy Character symbols letters

- Table of Contents:

Jade in Japanese (Katakana, Hiragana et Romaji) – jeido, ジェード, じぇーど

- Article author: www.popular-babynames.com

- Reviews from users: 42901

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.7

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Jade in Japanese (Katakana, Hiragana et Romaji) – jeido, ジェード, じぇーど How Jade first name is shown in Japanese? The answer is here and you will also be able to download the complete image of its representation in Romanji, … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Jade in Japanese (Katakana, Hiragana et Romaji) – jeido, ジェード, じぇーど How Jade first name is shown in Japanese? The answer is here and you will also be able to download the complete image of its representation in Romanji, … How Jade first name is shown in Japanese? The answer is here and you will also be able to download the complete image of its representation in Romanji, Katakana and / or Hiragana.jade,name,Japanese,katakana,hiragana,romanji

- Table of Contents:

Render for Jade (standard image)

Customized products for the first name Jade

jade in Japanese? How to use jade in Japanese. Learn Japanese

- Article author: wikilanguages.net

- Reviews from users: 28915

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.9

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about jade in Japanese? How to use jade in Japanese. Learn Japanese This is your most common way to say jade in ヒスイ language. Click audio icon to pronounce jade in Japanese:: … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for jade in Japanese? How to use jade in Japanese. Learn Japanese This is your most common way to say jade in ヒスイ language. Click audio icon to pronounce jade in Japanese:: … jade in Japanese? How to use jade in Japanese. Now let’s learn how to say jade in Japanese and how to write jade in Japanese. Alphabet in Japanese, Japanese language code.

- Table of Contents:

How to use jade in Japanese

Why we should learn Japanese language

How to say jade in Japanese

How to write in Japanese

Alphabet in Japanese

About Japanese language

Japanese language code

Conclusion on jade in Japanese

All Dictionary for you

English Japanese DictionaryJapanese

Japanese Word Images for the word Jade | Japanese Word Characters and Images

- Article author: www.japanesewordswriting.com

- Reviews from users: 46863

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.1

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Japanese Word Images for the word Jade | Japanese Word Characters and Images Here are some Japanese word images for the word “Jade”. In Japan we use the words “翡翠(ひすい-hisui)” for translating this word into … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Japanese Word Images for the word Jade | Japanese Word Characters and Images Here are some Japanese word images for the word “Jade”. In Japan we use the words “翡翠(ひすい-hisui)” for translating this word into … Japanese Word Images for the word JadeHere are some Japanese word images for the word "Jade". In Japan we use Uncategorized

- Table of Contents:

Related Posts

Comments

Jade in Japanese Tattoo Designs

- Article author: www.stockkanji.com

- Reviews from users: 49847

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.1

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Jade in Japanese Tattoo Designs Remember that names are translated to Japanese by how they are pronounced. So these Japanese Tattoo designs of Jade are only correct for … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Jade in Japanese Tattoo Designs Remember that names are translated to Japanese by how they are pronounced. So these Japanese Tattoo designs of Jade are only correct for … Jade Japanese Tattoo Designs by Master Eri Takase. Authentic designs including Jade is My Life, Jade is My Love, and Jade is My SoulMate. Jade Japanese Tattoo

- Table of Contents:

How to say jade in Japanese

- Article author: www.wordhippo.com

- Reviews from users: 7053

Ratings

- Top rated: 4.5

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about How to say jade in Japanese How to say jade in Japanese ; shrew noun ; 首を絞める, とがれねずみ ; hussy noun ; おしゃれな, 浮気女 … …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for How to say jade in Japanese How to say jade in Japanese ; shrew noun ; 首を絞める, とがれねずみ ; hussy noun ; おしゃれな, 浮気女 … Need to translate “jade” to Japanese? Here are 4 ways to say it.Japanese translation translate jade

- Table of Contents:

Jade – English to Japanese Translation of Jade | Japanese Dictionary – Free English to Japanese Dictionary

- Article author: japanesedictionary.org

- Reviews from users: 11313

Ratings

- Top rated: 3.5

- Lowest rated: 1

- Summary of article content: Articles about Jade – English to Japanese Translation of Jade | Japanese Dictionary – Free English to Japanese Dictionary English, jade. Type, noun. Japanese, 翡翠. Hiragana, ひすい. Pronunciation, hisui. Example. pure jade: 純粋な翡翠. Search. Search. …

- Most searched keywords: Whether you are looking for Jade – English to Japanese Translation of Jade | Japanese Dictionary – Free English to Japanese Dictionary English, jade. Type, noun. Japanese, 翡翠. Hiragana, ひすい. Pronunciation, hisui. Example. pure jade: 純粋な翡翠. Search. Search. Find Japanese words and Japanese phrases, learn their translation online with our English to Japanese Dictionaryjapanese, language, translation, translate, language learning, language translation, japanese dictionary, learn japanese

- Table of Contents:

See more articles in the same category here: 670+ tips for you.

Write Your Name In Japanese – Learn How to Write Your Name in Japanese

If you’re learning Japanese, one of the first things you should learn is how to introduce yourself! And you can’t do that unless you know your name in Japanese, right? Here is how to write your name in Japanese!

Introduction to Katakana

Japanese actually has 3 alphabets – Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji. While Japanese names are written in Kanji, foreign names are written in Katakana. Foreign names are typically spelled out with katakana to make them match phonetically with Japanese. Andrew becomes Andoryuu ( アンドリュー) , Brad becomes Buraddo (ブラッド) , and Carly becomes Kaarii (カーリー) .

One benefit of writing foreign names with katakana is that the reading and pronunciation is obvious for Japanese people, and just by looking at it, people also automatically know that it’s a foreign name. And, if you have a fairly common name, then chances are there’s a standard way of writing your name in katakana that Japanese people are already familiar with.

Katakana Chart

To write your name in Japanese, the easiest way is to find a Katakana letter that corresponds to the pronunciation of your Japanese name.

For example, if your name is “Maria,” look for the Katakana character for Ma, which is マ, then the character for Ri, which is リ, and then character for A, which is ア. You just need to put them together and write マリア for “Maria.”

Many foreign names have long vowels in them, such as Danny (Danī) or Nicole (Nikōru). In katakana, the long vowels (ā, ē, ī, ō, ū) are expressed with a hyphen. Danny is ダニー and Nicole is written as ニコール.

Also, keep in mind that L-sounds are turned into R’s to fit the Japanese alphabet sounds. So, Lauren becomes Rōren (ローレン) and Tyler becomes Tairā (タイラー).

Now you try! Use a Katakana chart like the one below:

Common Names

Here is a list of common foreign names that have been written out in Japanese katakana. Looking at these will help you figure out how your name should be pronounced in Japanese as well!

Male Names:

Alexander (Arekusandā) –> アレクサンダー

Bryan (Buraian) –> ブライアン

Chris (Kurisu) –> クリス

Daniel (Danieru) –> ダニエル

Harry (Harī) –> ハリー

John (Jyon) –> ジョン

Kyle (Kairu) –> カイル

Noah (Noa) –> ノア

Tom (Tomu) –> トム

William (Uiriamu) –> ウィリアム

Female Names:

Alexandria (Arekusandoria) –> アレクサンドリア

Brittany (Buritonī) –> ブリトニー

Elizabeth (Erizabesu) –> エリザベス

Emily (Emirī) –> エミリー

Hannah (Hanna) –> ハンナ

Jessica (Jeshika) –> ジェシカ

Kelsey (Kerushī) –> ケルシー

Lauren (Rōren) –> ローレン

Meghan (Mēgan) –> メーガン

Sarah (Sara) –> サラ

Last Names:

Anderson (Andāson) –> アンダーソン

Brown (Buraun) –> ブラウン

Davis (Deibisu) –> デイビス

Garcia (Garushia) –> ガルシア

Hernandez (Herunandezu) –> ヘルナンデス

Jones (Jōnzu) –> ジョーンズ

Martin (Mātin) –> マーティン

Miller (Mirā) –> ミラー

Smith (Sumisu) –> スミス

Williams (Uiriamuzu) –> ウィリアムズ

Writing Your Full Name

When writing both first and last names together in Japanese, the names should be separated by this symbol: ・

For example, Allison Wilson (Arison Uiruson) would be written as アリソン・ウィルソン, and Jose Hernandez (Hose Herunandesu) is written as ホセ・ヘルナンデス.

And that’s it! You now have all the tools you need to both say and write your name in Japanese. Be sure to introduce yourself to new friends you meet when you visit Japan!

Love Japan?

How to write Katakana YouTube playlist

Perfect Gift for your family, friends and yourself ♥in Katakana, Kanji & English

Japanese Jadeite: History, Characteristics, and Comparison with Other Sources

Figure 1. A large, attractive jadeite boulder from Itoigawa, Japan, characterized by mixed white and green colors. This boulder weighs 40.5 kg and measures approximately 39 cm high, 32 cm long, and 26 cm wide. Photo by Ahmadjan Abduriyim.

ABSTRACT

Even though Japanese jadeite lacks the transparency of the highest-quality Burmese imperial jadeite, its rarity and natural features make it a highly valued gemstone. In this study, jadeite from the Itoigawa and Omi regions in Niigata Prefecture and the Wakasa region in Tottori Prefecture, both on Japan’s western coast, were divided into several color varieties corresponding to chromophores and mineral phases: white (nearly pure jadeite), green (Fe-rich, Cr-bearing), lavender (Ti-bearing), blue (Ti- and Fe-bearing), and black (graphite-bearing). White jadeite from Itoigawa-Omi was close to pure jadeite (X Jd = 98, or 98% jadeite composition). Green jadeite from the same location had an X Jd range from 98 to 82. The maximum CaO content in green jadeite was 5 wt.%, and its chromophores were Fe and Cr. Whereas lavender samples had a jadeite composition of X Jd = 98 to 93 and tended to be high in TiO 2 and FeO tot and low in MnO content, blue jadeite showed the highest TiO 2 concentration at 0.65 wt.% and had an X Jd range of 97 to 93. A blue jadeite from Wakasa had a range of 97 to 91 and a similarly high TiO 2 concentration. In trace-element analysis, chondrite-normalized and primitive mantle–normalized patterns in lavender, violetish blue, and blue jadeite from Japan showed higher large-ion lithophile element contents (Sr, Ba) and higher field strength element contents (Zr, Nb) than those in green jadeite, while white and black jadeite had relatively low REE contents. The Japanese jadeites were compared to samples from Myanmar, Guatemala, and Russia.

INTRODUCTION

Japan is an important source of jadeite, much of which comes from the Itoigawa and Omi regions in Niigata Prefecture. The Kotaki area upstream of the Hime River in Itoigawa-Omi was the first documented source of gem-quality jadeite and jadeite-bearing rocks in Japan (Kawano, 1939; Ohmori, 1939). This area is located in the high-pressure, low-temperature metamorphic Renge belt within a Late Paleozoic subduction zone (Shibata and Nozawa, 1968; Nishimura, 1998). Tsujimori (2002) suggested that blueschist to eclogite metamorphism was related to the subduction of oceanic crust. Miyajima et al. (1999, 2001, 2002) and Morishita (2005) proposed that the fluids that facilitated the formation of jadeite in Itoigawa-Omi were related to subduction zones. U-Pb zircon dating of jadeite-natrolite rocks in the area indicated that the age of jadeitization is about 519 ± 17 Ma (Kunugiza et al., 2002; Tsutsumi et al., 2010).

This study introduces the historical background and sources of Japanese jadeite (figure 1). It describes the material’s color varieties, internal texture, and chemical features using quantitative electron microprobe (EPMA) and laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectroscopy (LA-ICP‐MS) analysis.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In addition to Japan, major jadeite localities include Myanmar, Russia, Central America, and the United States. Some of the world’s earliest jadeite jade artifacts emerged from the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations of modern-day Mexico and Guatemala, which flourished from about 1200 BC until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century (Foshag and Leslie, 1955; Umehara, 1971; Taube, 2004). During the Jomon era, about 5,500 years ago, Japan’s Itoigawa region became the birthplace of jadeite carving (figure 2), and it is no exaggeration to say that the Japanese gem culture was derived from this area. In the middle of the Jomon era, pendant-like jadeite pieces called taishu were produced and traded throughout many parts of Japan. Rough jadeite fashioning techniques, including spherical bead carving, were passed on in the late Jomon era. In the Yayoi era, curved magatama and tube-shaped kudatama beads became popular. According to legend dating from the early 8th century, the ancient state of Koshi (in modern-day Niigata Prefecture) was ruled by a beautiful empress who wore a mysterious curved green jadeite (figure 3). Koshi produced a variety of beautiful stones and cultivated a thriving trade with many other parts of Japan. Typically excavated from the tombs of powerful people, magatama jadeite appears to have been a sacred ornament as well as a symbol of wealth and prestige. Magatama carvings spread to the Korean Peninsula, where they have been excavated at many archaeological sites (Barnes, 1999).

Thousands of years of jadeite culture went into decline during the mid and late Kofun period (3rd to 7th century AD) before disappearing in the 6th century. Jadeite was rediscovered in Japan in 1938, more than a thousand years after vanishing, when researcher Eizo Ito uncovered it at the Kotaki River in the city of Itoigawa. The following year, Dr. Yoshinori Kawano and his colleagues at Tohoku University published a study of the samples (Kawano, 1939; Ohmori, 1939). Subsequent research led to additional discoveries in the Kotaki area, upstream of the Hime River, as well as in the Hashidate area of Itoigawa (figure 4). In 1954, some of these areas were designated as preservation sites, but jadeite is still found along these rivers or their estuaries.

Jadeite from Itoigawa, especially along the coast, is beautiful even in its rough state. Colors include white, green, violet, blue, and black. But because the sites are protected and mining is not allowed, there is little supply of this material in the market. In September 2016, Itoigawa jadeite was chosen as Japan’s national stone by the Japan Association of Mineralogical Sciences.

JADEITE FROM JAPANESE LOCALITIES

Jadeite is found in high-pressure, low-temperature metamorphic belts (Essene, 1967; Chihara, 1971; Harlow and Sorensen, 2005). It is associated with kyanite, an indicator mineral of high-pressure, low-temperature metamorphism. The Japan Trench is a boundary between the Pacific plate and the Eurasia plate containing the Japanese islands, under which the cold Pacific plate subducts. This area is thought to have a high-pressure, low-temperature condition that produces jadeite. Japan has eight jadeite occurrences in all (again, see figure 2). Most of the jadeite from the Renge and Sangun belts on the western side (Itoigawa, Oosa, Oya, and Wakasa) is very pure, composed of more than 90% jadeite (including similar omphacite). Material from other parts of Japan very rarely contains more than 80% jadeite. Most contains large amounts of albite, kyanite, and analcime and no more than 50% jadeite (Yokoyama and Sameshima, 1982; Takayama, 1986; Miyazoe et al., 2009; Fukuyama et al., 2013).

Renge and Sangun Belts. The Itoigawa region is assigned to the Renge belt, a serpentinite mélange zone with various types of tectonic blocks, high-pressure and low-temperature metamorphic rocks, metamorphosed sedimentary rocks, amphibolites, and rodingites (Nakamizu et al., 1989). Gem-quality jadeite has been found only at the Kotaki and Hashidate districts in Itoigawa-Omi, occurring as boulders in the serpentinite located at the fault border between the Permian-Carboniferous limestone and Cretaceous sandstone and shale. Jadeite boulders range from one meter to several meters in size and are mostly distributed in an area several hundred meters long. Jadeite rocks in Kotaki show concentric zoning, toward the rim, of albitite (with or without quartz), white jadeite, green jadeite, soda-rich calciferous amphibole, and host serpentinite. Omi jadeite rock shows a “distinct stratiform structure,” sometimes with alternating coarse and fine compact layers and often containing lavender jadeite (Chihara, 1991).

Sources other than Itoigawa in the Renge and Sangun belts (Oosa, Oya, and Wakasa) produce limited amounts of jadeite, most of it white with a few green areas. Green jadeite with high transparency has not been found in these areas. Considering that it contains similar minerals as well as zircons that are about 500 million years old (Tsutsumi et al., 2010), the material from Oosa, Oya, and Wakasa presumably formed through the same process as the Itoigawa jadeite. These fine-grained specimens cannot be differentiated microscopically from those of Itoigawa.

The Wakasa region in Tottori Prefecture of western Japan is a source of blue jadeite. Jadeite and jadeite pyroxene occur in serpentinites and metagabbros related to the Sangun regional metamorphic belt (Kanmera et al., 1980; Chihara, 1991). In this locality, jadeite rock formed as a vein in part of a serpentinite body ranging from 5 to 30 cm in diameter. The rocks are mostly weathered but still hard and compact. Most of the jadeite has a violetish blue to blue, lavender, and milky white color and is associated with albite, quartz, and chlorite. Wakasa jadeite is also known to have a blue color, but production is very limited.

Hokkaido. The northern Japanese island of Hokkaido is shown in figure 2. The Kamuikotan belt, a high-pressure metamorphic belt, extends north to south in Hokkaido. In the serpentine area of this metamorphic belt in the Asahikawa district, jadeite-bearing rocks are very rare but may locally contain more than 80% jadeite. Most of the jadeite around 10 cm in size contains less than 50% jadeite content, however. Various mineral components deprive the jadeites of their transparency, making them difficult to distinguish from surrounding green rocks of lawsonite-albite facies retrograded in greenschist facies.

Sanbagawa Belt. Two deposits of jadeite-bearing rock have been reported in the Yorii and Chichibu districts in the Kanto Mountains of Saitama Prefecture. One of the locations forms a dome with serpentine, and the maximum jadeite content there is about 50%. Another occurrence, accompanied by actinolite rocks that supposedly replaced serpentinite, is similar to the surrounding metamorphic rocks where jadeite occurs in clusters, and samples with more than 80% jadeite content are rare. The jadeite from this area is not suitable for jewelry and, like material from Hokkaido, cannot be differentiated from the surrounding metamorphic rocks. Mikkabi in Shizuoka Prefecture also produces jadeite, found as a white vein 2 to 3 cm thick in metagabbro, but it too is unsuitable for fashioning.

Kochi and Nagasaki. Rocks containing jadeite have occasionally been found within serpentinite in the city of Kochi. These include gray quartz-bearing rocks and green rocks containing pumpellyite and kyanite. Neither contains more than 60% jadeite or possesses transparency, and thus cannot be visually differentiated from common hard metamorphic rocks. In Nagasaki, rocks containing jadeite associated with serpentine have been reported. Parts of the rock contain more than 80% jadeite, but the content is often as low as 50%. Only limited amounts of the jadeite-bearing rocks have been produced.

SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS AND ANALYTICAL METHODS

To examine the color varieties of Japanese jadeite, we collected representative samples from the field in Itoigawa and Wakasa and from the Jade Ore Museum (Hisui Genseki Kan) in Tokyo and the Fossa Magna Museum in Itoigawa (see the top table at https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/spring-2017-japanese-jadeite-tables). The 39 rough and cut Japanese samples consisted of white, green, dark green, lavender, violetish blue, blue, and black jadeite. They were from three different sources: the Kotaki River area (36º55’33N, 137º49’18E; 32 samples) and Hashidate (36º58’35N, 137º45’51E; five samples), both in Itoigawa, and the Wakasa region (35º32’17N, 134º44’52E; two samples).

To compare their optical features, petrographic structures, and geochemistry with samples from other parts of the world, we also tested Russian white and green jadeite from the Polar Urals (four samples); dark yellowish green and lavender jadeite from the Motagua region of Guatemala (six samples); and Burmese white, green, and lavender jadeite from Kachin State (38 samples). The samples were provided by the Jade Ore Museum (Hisui Gensekikan) and Miyuki Co., Ltd. Examples are shown in figure 5.

All 87 samples were observed by visual and microscopic means, and their refractive indices were examined by either normal reading from flat wafers or by the spot method. Specific gravity was determined hydrostatically for all the samples, and their absorption spectra were observed by handheld prism spectroscope. Four inclusion-bearing samples from Itoigawa and Wakasa, three from Kachin, two from Motagua, and two from the Polar Urals were cut and polished into thin sections for petrographic structure analysis. The micro-texture of these petrographic thin sections was observed using a Nikon Optiphot polarized light microscope.

To identify the inclusions and reveal the distribution of jadeite and other minerals in jadeite rock, we used a two-dimensional micro-Raman mapping spectroscope (Horiba Jobin Yvon XploRA LabRAM HR Evolution) equipped with a 532 nm Nd:YAG laser and an optical microscope (Olympus BX41) under real usage conditions. The laser beam was narrowed and focused through a 300 μm aperture and a 100× objective lens, yielding a spatial resolution of about 1 μm. Raman spectra were acquired with a single polychrome spectrometer equipped with a Si-based charge-coupled device (CCD) detector (1024 × 256 pixels). A composite spectrum in the range of 200–1800 cm–1 was obtained with LabSpec software, using a 600 gr/mm grating with a spectral resolution of about ± 2.5 to 3.5 cm–1. Before performing the measurements, we calibrated the spectrometer by the Si 520 cm–1 peak. Raman spectral mapping was conducted in point-by-point macro mode using XY stepping motors. It took 15 minutes to obtain a 44 × 30 mm spectral macro mapping image with a step size of 500 μm in the 200–1800 cm–1 range.

UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy was performed on parallel polished wafers of green, lavender, and blue samples from Kotaki, Itoigawa; a violetish blue sample from the Wakasa region; green and lavender samples from Kachin and Motagua; and a green sample from the Polar Urals. The analyses were performed using a Hitachi U-2900 spectrophotometer at 1 nm resolution. The parallel polished plates were oriented with the main polished face perpendicular to the instrument beam, and the polarizer was not rotated. The thin sections ranged from 3.63 to 10.08 ct and from 0.86 to 3.70 mm thick.

To investigate the various colors of the jadeites, very precise quantitative chemical composition measurements were obtained by electron microprobe with wavelength-dispersive spectrometry (WDS) mode (JEOL LXA-8900) at the University of Tokyo and Waseda University. Eleven thin sections and polished thin plates from Itoigawa and Wakasa, two specimens from Motagua, and one specimen from the Polar Urals were analyzed with 15 kV accelerating voltage, using a beam current of 12 nA and beam diameter of 10 μm. Data were processed with ZAF correction software. The standards were natural albite for Al(Kα) and Na(Kα), wollastonite for Ca(Kα) and Si(Kα), orthoclase for K(Kα), chromite for Cr(Kα), Mn-olivine for Mn(Kα), and TiO 2 , Fe 2 O 3 , MgO, and NiO for Ti(Kα), Fe(Kα), Mg(Kα), and Ni(Kα), respectively.

Trace element and rare earth element (REE) analyses were performed with LA-ICP-MS using a Thermo Scientific iCAP Q quadrupole ICP-MS with an ESI UP213 Nd-YAG laser. The laser repetition rate was 7 Hz, with an energy density of 10 J/cm2 and a spot size of 40 μm, using a carrier gas mixture of helium and argon. It was possible to detect the signal of all isotope ratios and achieve an analytical precision of less than 10% relative standard deviation (RSD). Three to ten spots were ablated for each sample, and averaged data was calibrated. NIST SRM 610 and 612 were used as external standards. Before analysis, the samples were cleaned with acetone and aqua regia in an ultrasonic bath to eliminate surface contamination.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Gemological Observations. Jadeite pebbles from Itoigawa-Omi tend to have rounded corners, resulting from erosion by fluvial processes, and a glittering whitish surface. Because of surface weathering, the rough rock does not have a brown skin. These stones are mainly white, with unevenly distributed pale green to green areas, and they feel rigid, compact, and heavy. Most of the white rocks mixed with some green were in boulder, pebble, and nodule form, transparent to semi-translucent to opaque, and finely textured, with some coarse texture in eye-visible single crystals. The largest rough specimen, found in the Hashidate district, weighed 102 tons. The author has also observed a 4.6 ton jadeite rock from the Kotaki district that is housed in the Fossa Magna Museum (figure 6, left). In this large jadeite boulder, most of the white and green parts were jadeite jade, while the fibrous black portion was composed of amphibole. Some small green areas were translucent and gemmy. Some minor faults were filled with white minerals such as prehnite, pectolite, and zeolite-group minerals that formed within fluids from the deeper part of the earth.

In lavender jade, the violet color may be dispersed irregularly over the white matrix. This color is semi-translucent to opaque, with a fine to medium texture (figure 6, center). The blue jadeite samples, found in a variety of beautiful colors, were rounded and semi-translucent to opaque, with fine to coarse texture (figure 6, right). Aggregates of minute crystals were observed through a loupe but lacked crystal form. Specimens from Itoigawa and Tottori had a spot RI of 1.65 to 1.66 and SG values ranging from 3.10 to 3.35. Green jadeite samples were inert under long-wave (365 nm) and short-wave (254 nm) UV radiation. The lavender jadeite exhibited a stronger reddish fluorescence than Burmese lavender jadeite, which showed a weak reddish fluorescence to long-wave UV. The Japanese blue jadeite was inert to both long- and short-wave UV. The absorption spectra of all Japanese jadeite samples, measured by a handheld spectroscope, revealed weaker lines at 690, 650, and 630 nm. In addition, green jadeite from Itoigawa showed a very sharp line at 437 nm. The lavender jadeite showed weak bands at around 530 and 600 nm and a narrow band at 437 nm. The blue jadeite showed a very broad band from the yellow to red portion of the spectrum, as well as a weak narrow band at 437 nm.

The representative Guatemalan jadeite samples selected for this study were grayish and dark green, white, and violetish blue. The green rough was semi-translucent and opaque, with a fine to medium-grained texture but also somewhat coarsely grained texture in visible crystals. The “Olmec blue” rough from Guatemala was variegated violet to blue mixed with abundant white color. It was translucent to opaque, with a fine texture. Its color distribution closely resembled that of Japanese lavender and blue jade.

Jadeite from the Polar Urals occurs in different shades of green. The material usually has a more even color distribution than Japanese green jadeite, and it is highly valued. The samples from this source were semitransparent to translucent, with a fine to medium texture. Black spots of magnetite could be observed.

Petrographic Observation. In plane-polarized light, a white and green jadeite slice from Itoigawa (K-IT-JP-14; see figure 7-A1) revealed colorless, semitransparent jadeite crystals distributed in the white area, mostly as fine cryptocrystalline grains around 0.05–0.3 mm in size. Under cross-polarized light, the fine jadeite grains showed both high- and low-order interference colors, caused by the different orientation of each grain. Under plane-polarized light, we occasionally observed in matrix large pale green grains over 2 mm (figure 7-A2) that were well-formed jadeite single crystals. Their well-developed cleavages intersected at 87° angles, which is characteristic of pyroxene. This thin section of green jadeite showed a prismatic crystalloblastic texture, indicating metamorphism under nondirectional pressure. Micro-Raman spectrometry in microfolds and veinlets identified minor amounts of pectolite and prehnite as component minerals.

The thin section of lavender jadeite from Itoigawa-Omi was almost colorless under plane-polarized light (see figure 7-B1). The sample was semi-transparent to translucent and mainly composed of fine to micro-grained crystals around 0.1–0.3 mm in size, showing a prismatic crystalloblastic texture. Ultramylonitic zones with radiating aggregates of fine jadeite grains randomly cutting through the matrix were observed in this sample (figure 7-B2). This texture indicates that the sample underwent lithostatic and possibly subsequent directional pressure during the metamorphic process. Prehnite and analcime, the main constituents of the veinlets that cut through the jadeite rock (figure 7-B3), were formed by hydrothermal fluids (Shoji and Kobayashi, 1988). A long prismatic vesuvianite crystal with high relief was also found as a component mineral.

In the blue jadeite sample (K-IT-JP-16), the blue area was larger than the white area, and the colors gradually blended. It was translucent and granular, and the fine cryptocrystalline grains from 0.1 to 0.5 mm (figure 7-C1) showed granoblastic and mylonitic texture. In this specimen, preexisting minerals were crushed and slipped to produce a flow structure (figure 7-C2). Component minerals included analcime and titanite, as well as very minor amounts of euhedral titanite grains in the matrix that do not contribute to the blue color in this type of jadeite.

Morishita et al. (2007) proposed that jadeite from Itoigawa-Omi formed either by direct precipitation of minerals from aqueous fluids or by complete metasomatic modification of the precursor rocks by fluids. The Burmese green and lavender jadeite samples showed amphibole, albite, kosmochlor, and nepheline, while vesuvianite was rare. The Guatemalan green and lavender jadeite in this study showed grossular garnet, albite, and rutile, while the Russian green jadeite contained magnetite and analcime.

We used two-dimensional point-by-point Raman macro mapping to reveal the distribution of jadeite and other component minerals in the jadeite rocks. Figure 8 shows a white and green/dark green sample from Itoigawa; the red, green, and blue colors correspond to the integrated intensity of jadeite, amphibole (richterite), and prehnite, respectively. This image reveals that the jadeite and amphibole grains are mixed within the matrix, while prehnite occurs in the vein. The rapid point-by-point confocal mapping technique can be performed on a whole specimen or a region of interest to examine finer details, making it possible to classify the distribution of jadeite vs. omphacite and/or amphibole.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy. Japan. UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy was performed on the green, violet, violetish blue, and blue jadeite wafers from the Itoigawa-Omi and Wakasa regions. Chemical analysis was carried out on similarly colored areas of the sample to confirm each chromophore’s concentration.

Green portions of Itoigawa jadeite are generally colored by chromium and iron, showing a 691 nm absorption line (the Cr3+ “chromium line”) and another absorption line that originates at around 437 nm (the Fe3+ “jadeite line”); see figure 9. The chromophore concentrations in the tested area, a 5 mm circle, were analyzed by LA-ICP-MS, and a concentration was averaged from three to four laser ablation spots. The green area contained relatively high Cr and Fe (280 and 810 ppma), and the isovalent chromophores Cr3+ and Fe3+ clearly contributed to the green color (Rossman, 1974; Harlow and Olds, 1987). The less significant chromophores Ti, Mn, V, and Co had lower concentrations (57, 19, 2.3, and 0.4 ppma, respectively; see the bottom table at https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/spring-2017-japanese-jadeite-tables).

The UV-Vis spectra of lavender jadeite from Itoigawa-Omi show features that correspond with Mn, Ti, and Fe (figure 10). A broad Mn3+-related absorption band centered at 530 nm is often observed in Burmese lavender jadeite (Lu, 2012), as well as a characteristic broad band of paired Ti4+-Fe2+ charge-transfer ions centered at 610 nm and a narrow Fe3+-related 437 nm absorption band. The color-causing transition elements were analyzed in this lavender jadeite. The results showed that Ti (534 ppma average) and Fe (550 ppma average) were clearly responsible for its blue hue. Mn concentrations averaged 18 ppma and produced a weak pink or purple hue. The Japanese lavender jadeite showed a violet color, owing to the combination of minor pink and significant blue hues caused by Mn3+ and Ti4+-Fe2+ absorption.

Shinno and Oba (1993) discussed the substitution of Ti3+ at 545 nm in lavender jadeite from Itoigawa-Omi. However, the Ti3+ ion is very unstable in nature and is found only in meteorites and lunar samples formed in more reducing conditions (Burns, 1981). In terms of ionic radius, isovalent Ti3+ is noticeably larger than Al3+ and does not replace it in the six-fold coordinated octahedral site (figure 11). The chromophore concentrations of Ti and Fe in the violet parts reached 550 and 534 ppma, and this combination caused a noticeable blue color.

The UV-Vis spectra of blue jadeite from Itoigawa show a very broad band from 500 to 750 nm, a weak Fe3+ absorption at 437 nm, and a cutoff above 350 nm (figure 12). This absorption pattern is similar to the spectra of blue sapphire and can be attributed to a charge transfer between Ti4+-Fe2+ pairs (Ferguson and Fielding, 1971). Significant amounts of Ti (1943 ppma) and Fe (4212 ppma) produced a noticeable blue color. By comparison, Mn was too low (64 ppma) to produce a pinkish component.

The violetish blue jadeite from Wakasa in Tottori Prefecture showed a similar spectral characteristic, with lower Ti, Fe, and Mn concentrations than blue jadeite but higher concentrations than violet jadeite from Itoigawa (see the bottom table at https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/spring-2017-japanese-jadeite-tables).

Myanmar. The UV-Vis spectrum of the Burmese green jadeite (K-MYA-16) showed the characteristic narrow Cr3+-related absorption band at 691 nm and the sharp, narrow Fe3+-related absorption band at 437 nm that is very common in natural green jadeite. The Cr and Fe absorption feature generally overlapped with the spectrum of Japanese green jadeite, but the absorption intensity was much higher in Burmese jadeite due to its color saturation and transparency (figure 13A). The Burmese lavender jadeite (K-MYA-20) with a predominantly purple color component had a broad absorption centered at 570 nm, related to Mn concentration (figure 13B). The Fe and Ti concentration was much lower than in Japanese lavender jadeite and might not cause any noticeable blue component.

Guatemala. Only the characteristic Fe3+-related narrow absorption band at 437 nm was found in the Guatemalan grayish green jadeite spectrum, which lacked the Cr3+ absorption (figure 13C). A very closely matched absorption spectrum was observed in Guatemalan lavender jadeite, which showed multiple broad bands centered at 530 and 610 nm and a weak narrow band at 437 nm (figure 13D). This absorption feature, related to Mn3+, Ti4+-Fe2+ pairs, and Fe3+, generally overlapped with the bands observed in Itoigawa lavender jadeite. The concentrations of V, Cr, and Co were too low to create any noticeable color.

Russia. A highly saturated vivid green jadeite from the Polar Urals showed an Fe3+ band and strong multiple chromium lines in the 580–700 nm range, a combination that typically produces a highly saturated green color (figure 13E). The Cr concentration (up to 3042 ppma) was much higher than in Japanese green jadeite.

Chemical Analysis. Quantitative chemical data collected by EPMA for the samples from Japan, Guatemala, and Russia are summarized in table 1. The results are described below for each representative color: white, green, lavender, and blue (including violetish blue). X Jd , X (Ae+Ko) , and X Quad (Dio+Aug+Hed) were calculated as mol.% of Al/(Na + Ca), Fe3+/(Na + Ca), and Ca/(Na + Ca), respectively (figure 14). The highest and lowest concentrations of jadeite (X Jd ) for 11 tested samples are listed in table 1. The 87 specimens from the four countries in this study (Japan, Myanmar, Guatemala, and Russia) were analyzed by LA-ICP-MS, with averaged data calculated based on three to ten laser ablation spots for each specimen; minimum and maximum values of each element concentration are listed in the bottom table at https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/spring-2017-japanese-jadeite-tables, with averaged data in parentheses.

White Jadeite. White jadeite from Itoigawa belongs to the clinopyroxene group and is close to the ideal jadeite composition (again, see table 1). All analyses (more than five spots) were close to the end member composition, up to X Jd = 98 mol.%. The CaO, MgO, and FeO tot contents were lower than those tested from any other jade color (0.26, 0.12, and 0.44 wt.%, respectively). Values for Cr 2 O 3 , MnO, K 2 O, and NiO were below the detection limit of the analysis. TiO 2 (0.03 wt.%) was lower than values analyzed from violet and blue jadeite elsewhere. The white jadeite was very pure.

LA-ICP-MS analyses of the white jadeite consistently identified 19 minor and trace elements (Li, Mg, K, Ca, Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, Sc, Ni, Zn, Ga, Se, Sr, and Zr). Other trace elements (B, Rb, Y, Nb, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu, Hf, Ta, W, Th, and U) were above the detection limits. Although Itoigawa “white” jadeite generally had lower Mg and Ca contents (3841 and 8495 ppmw, respectively) than green, blue, and black jadeite, almost all of the detectable minor and trace element contents were higher than in white jadeite from Kachin State in Myanmar (see the bottom table at https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/spring-2017-japanese-jadeite-tables).

Green Jadeite. Microprobe analyses of four green jadeites revealed significant Fe content, from a minimum value of 0.22 wt.% to a maximum of 0.864 wt.%, and a slightly low Cr value of 0.01–0.57 wt.%. Values for MgO (0.16–2.83 wt.%) and CaO (0.24–4.18 wt.%) were relatively high, but the compositions fit within the jadeite range of X Jd = 98.7 to 82.4 (figure 15). Samples from Itoigawa-Omi showed slight differences in major element composition between crystal aggregates and discrete single-mineral grains. This study indicates that the green jadeite is also nearly pure jadeite, though some discrete single-mineral grains showed a composition closer to omphacite within the jadeite-dominant matrix.

The 13 green specimens from Itoigawa revealed the remarkable transport of large-ion lithophile elements in subduction zones, such as Li, B, K, Sr, and Ba, as well as elements that are considered more refractory, such as rare earth elements (La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu) and Hf, Ta, W, Tl, Pb, Th, and U. The Mg and Ca contents were also relatively high, ranging from 2383 to 77,100 ppmw for Mg (averaged to 19,957 ppmw) and 4400 to 82,700 ppmw for Ca (averaged to 39,206 ppmw). Mg and Ca contents were much higher in the dark green areas, which indicates that the dark green omphacite component is more abundant in trace elements (except Li and Ga) than jadeite. To establish a useful chemical fingerprint diagram for separating omphacite jade from jadeite jade, we plotted two different combinations of major and minor elements. As seen in figure 16, plotting Al/Fe vs. Ca/Na clearly separates the jadeite according to chemical concentration.

By comparison, the green samples from Itoigawa-Omi showed higher Li, B, Mg, K, Ca, Ni, and Sr than green jadeite from Myanmar, while the transition metal elements Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, and Co showed similar ranges. Ti and Fe were dominant in Russian and Guatemalan green jadeite. The Russian green jadeite showed the highest Cr content (up to 7940 ppmw, averaged to 2872 ppmw) of any samples.

Lavender Jadeite. EPMA performed on a violet sample from Itoigawa (K-IT-25) yielded significant TiO 2 (up to 0.362 wt.%) and FeO tot (up to 0.694 wt.%), whereas MnO was relatively low (up to 0.019 wt.%). The color of the Japanese lavender jadeite likewise should correlate to the chromophores Ti4+, Fe2+, and Mn3+. The contents of MgO (up to 0.864 wt.%) and CaO (up to 1.879 wt.%) were relatively low. The jadeite composition ranged from X Jd = 98.7 to 93.3, close to pure jadeite.

LA-ICP-MS detected noticeably high amounts of Ti and Fe in all of the violet jadeite. Other metal elements such as Li, B, K, Sr, and Ba, as well as REEs, were higher than in white or green jadeite from the same geological source in Itoigawa-Omi. Lavender jadeite from Guatemala showed a similar violetish hue, and trace element concentrations revealed similarly high levels of Ti and REEs. But the transition metal ions V, Cr, and Co were below detection limits, consistent with its original light violet color (Sorensen et al., 2003). By comparison, 16 Burmese lavender samples showed appreciable Mn, explaining their dominant pinkish/purplish component. Oberhänsli et al. (2007) did not observe a Ti phase in the high-pressure assemblage, which may contain the same accessory phases (amphibole, feldspar, and lawsonite) as jadeite from Itoigawa-Omi.

Blue Jadeite. The six blue samples from Itoigawa and the two violetish blue specimens from Wakasa had significantly high TiO 2 , with maximum values of 0.649 and 0.745 wt.%, respectively. These corresponded with the intense blue area. The CaO contents were slightly higher in the light blue to blue areas (0.6% to 1.4 wt.%) than in the white areas. Violetish blue and blue areas revealed the highest concentration of Ti measured in Japanese jadeite (up to 4520 ppmw in blue jadeite from Itoigawa, and up to 3636 ppmw in violetish blue jadeite from Wakasa), as well as enriched Fe (up to 11,900 ppmw). Most of the REE contents were higher than in lavender jadeite.

Chondrite-Normalized REE and Primitive Mantle–Normalized Heavy Trace Element Pattern. To compare trace element compositions in different colors of Japanese jadeite, we studied their chondrite-normalized REE patterns and primitive mantle–normalized trace element patterns. Figures 17 and 18 show the averaged REE and heavy trace element data of white, black, green, lavender, and blue jadeite from Itoigawa-Omi, along with two violetish blue specimens from Wakasa. The REEs in Japanese jadeite tended to be more abundant in lavender, violetish blue, and blue specimens than in green, white, and black jadeite. In all colors, the light rare earth element (LREE: La, Ce, Nd, and Sm) contents tended to be higher than the heavy rare earth element (HREE: Eu, Gd, Dy, Y, Er, Yb, and Lu) contents. From this chondrite-normalized REE pattern, the lavender, violetish blue, and blue jadeite from Japan can be characterized by a high LREE/HREE ratio and a low Eu concentration relative to other REE (again, see figure 17).

Interestingly, the primitive mantle–normalized trace element patterns of all colors of Japanese jadeite showed strong positive anomalies of the large-ion lithophile elements (LILE) Sr and Ba, as well as the high field strength elements (HFSE) Zr and Nb. Green jadeite REE patterns were more depleted, but much higher than white and black jadeite, with strong positive anomalies of Sr, Zr, and Hf. This result is consistent with the conclusion by Morishita et al. (2007) that the fluid related to the formation of Itoigawa-Omi jadeite in the subduction zone was uniquely enriched in both LILE1 and HFSE2 brought in by the fluids in the subduction zone, and that these elements were recycled into serpentinized peridotites.

By comparison, Russian white and green jadeite revealed the highest REE and heavy trace element values in this study. Green jadeite from Japan and Myanmar showed a very close overlap, whereas the REE and heavy element contents for white samples from Myanmar were very depleted and had the lowest value.

In lavender and blue samples, Guatemalan jadeite was characterized by the highest REE and heavy trace element concentrations. Japanese material showed a lower value but could be separated from Burmese lavender jadeite based on the chondrite-normalized and primitive mantle–normalized patterns.

CONCLUSIONS

Japanese jadeite from the Itoigawa-Omi region is characterized by mixtures of white with green and other colors such as lavender, blue, and black. Although jadeite mining has been prohibited there since 1954, small pebbles can be found along the rivers or estuaries. In this study, a large number of samples from Itoigawa-Omi and Wakasa were analyzed to characterize the chromophores, optical absorption features, and quantitative chemical composition of major and trace elements in each color variety. This gemological, petrographic, and chemical study also included Burmese, Guatemalan, and Russian jadeite samples for comparison. The results are summarized below.

Jadeite boulders and pebbles from Itoigawa-Omi tended to have rounded corners from fluvial erosion and showed a glittering whitish surface, but the rough rock did not show a weathered brown skin. The Japanese jadeite was mainly white, with unevenly distributed pale green to green and lavender to blue color. Petrographic observations showed that Japanese jadeite was composed of aggregates of long, semi-euhedral prismatic crystals and granular single crystals, which combined to produce a prismatic-granular crystalloblastic texture. Pectolite, prehnite, and analcime were often present in folding, faults, and veinlets, while the minor component minerals vesuvianite and titanite were found in the matrix. Quantitative analysis by electron microprobe showed that the white jadeite was close to pure jadeite (X Jd = 98). Green jadeite was in the range of X Jd =98–82 and X Aeg =2–8, and the chromophores Fe and Cr were responsible for the green color. Lavender color was produced by a combination of higher Ti and Fe and lower Mn. In blue jadeite, the Ti4+-Fe2+ charge-transfer played a significant role in coloration. LA-ICP-MS analysis detected 19 minor and trace elements. The chondrite-normalized rare earth element and primitive mantle–normalized heavy trace element patterns of all colored jadeite showed higher light REE than heavy REE, along with positive large-ion lithophile elements and high field strength element anomalies. Lavender and blue (including violetish blue) jadeite had dominant REE compared to green jadeite, whereas white and black jadeite had the lowest REE contents.

Our studies confirmed that green jadeite from Itoigawa, Myanmar, and Russia have similar gemological properties such as RI and SG and absorption spectra of Cr and Fe, while Guatemalan grayish green jadeite does not contain Cr. Lavender jadeite from Japan and Guatemala showed similar color, caused by high Ti and Fe and low Mn. Investigation of thin sections revealed that Burmese jadeite contains kosmochlor, amphibole, albite, nepheline, and vesuvianite. Russian jade has the very common mineral magnetite in matrix and analcime in veinlets. Guatemalan jadeite was characterized by grossular garnet, albite, rutile, and other minerals. While Guatemalan jadeite contained abundant REEs and heavy trace elements, Burmese jade had much lower values. Japanese jadeite shows characteristic trace elements and matrix inclusion varieties that may be useful in establishing the precise country of origin.

How to Ask “What Is Your Name?” in Japanese

Learn how to ask “What is your name?” in Japanese in this Howcast video with expert Kanasato.

Transcript

How to ask, “What is your name?” in Japanese.

Onamae wa nandesuka?

Let’s try it.

Onamae wa nandesuka?

Onamae wa nandesuka?

You can also say: Anata no onamae wa?

Onamae is “your name” or “the name,” and Anata is “you” or “your.”

So, you can say: Anata no onamae wa?

ADVERTISEMENT Thanks for watching! Visit Website

Let’s try it.

Anata no onamae wa?

Again.

Anata no onamae wa?

And that’s how to ask, “What is your name?” in Japanese.

So you have finished reading the how to write jade in japanese topic article, if you find this article useful, please share it. Thank you very much. See more: jade in japanese hiragana, jade in japanese katakana, japanese to english, hisui name meaning, jade in korean, jade in chinese, japanese word for jade dragon, jade in spanish